He’s All Fun and Games

News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

In his 40+year career as a lauded toy and game inventor, Robert Fuhrer of Chappaqua has brought to market more than 200 toys and games — from Crocodile Dentist to KenKen

Good morning! Today is Wednesday, May 4, and you are reading today’s section of Examiner+, a digital newsmagazine serving Westchester, Putnam, and the surrounding Hudson Valley.

Need to subscribe — or upgrade your Examiner+ subscription to enjoy full access to all of our premium digital content? Take advantage of our special FREE TRIAL OFFER.

Take Examiner+ on a test drive today at NO CHARGE for a full month. Enjoy full membership-level access to all of our premium local content, delivered straight to your inbox six times a week.

When I caught up with Robert Fuhrer on a Zoom call from his ocean-view condo on Singer Island in Florida, I learned about his decades-long toy-inventing collaboration with the Japanese, the advice he’d give folks who have cool new board game ideas, and what type of games go viral today. He also shared his take on how playing games can help bring our fractured world together.

Examiner+: So how does a person end up in the toy and games industry, maybe every kid’s dream?

Robert Fuhrer: I’ve been involved in this industry my whole life. My dad was an executive at Matchbox and Topper Toys, and I’d often spend time with him coming up with ideas for new toys. My favorite toys back then always had to do with guns and spy gear. When I graduated from Syracuse University, I was hired as product manager on the Othello strategy-game brand. My brother, David, is also in the toy industry and has had exceptional success selling new ideas—so being raised with the essence of toys around us obviously left a mark.

E+: Are you a Westchester native?

Fuhrer: I was born in the Bronx in 1955 but I grew up in Ardsley. Once, in high school, our team had a baseball game at Horace Greeley High School, and we did a caravan to get up there on the Saw Mill. I was like, Where are we going?! It seemed so far away. And then we got up to Horace Greeley High School, and I wondered, Is this a college? I was blown away by that campus. Now my wife, Judy, and I have lived in Chappaqua for close to 30 years, raising two sons and a daughter who all went to Greeley.

E+: When did you found your toy-and-game invention business, Nextoy?

Fuhrer: 1981. 9/9/81. A square root day.

E+: I love that.

Fuhrer: Yeah, there’s only one a decade. I’m a little superstitious about numbers. A lot of significant events in my life happen to have special numbers. I was bar mitzvahed on 6/8/68. My birthday is on 7/11. We made sure to launch our website for the numbers puzzle KenKen on 3/14 — Pi Day, a big day for numbers. I think numbers tell you the truth.

E+: You’ve worked closely with Japan and Asia on toy inventions, making the long treks east multiple times a year. How did that collaboration come about?

Fuhrer: When I was a young guy and just starting out in the business here in New York in the early 1980s, I met a Japanese executive from Asahi, a toy car company, who was interested in expanding their business into America. We had dinner together. He was a smart guy. He knew I was moldable and didn’t have that much going on yet.

He told me, “I’m going to give you a chance. My company, a big corporation in Japan, is not going to understand me working with you. So this is between us. If something positive happens, I will find a way to reward you, but you’re going to have to trust me.” He seemed to me to be very truthful and trustworthy.

So, he gave me a product and I sent it out to a few places in the U.S. Then I got a bite from a company that was working on something similar. This Japanese product was far more advanced and they wanted it. It was all new for me, I didn’t even know how to make the deal.

When it looked like something big was going to happen, I started telling the people in my immediate world. And my father and others were like, “Well, what’s your deal with this Japanese guy?” And I said, “Oh, he told me to trust him, he would take care of me.” And everyone said, “What? Are you an idiot?”

A lot of people got into my head about me being taken advantage of, and I started believing them. I wrote Mr. Shimakata a letter saying If this thing is going to happen, like what’s in it for me?

It was a bad letter, I know now. I got a letter back from him basically scolding me for bringing it up, saying in a very formal Japanese style I told you I’d take care of it, this is very frustrating for me. I oddly felt great about his letter; it felt real that he was scolding me, and I trusted him again.

After that deal took place, he said to me, “As part of your reward, we’re going to bring you to Japan.” It was my first time, and I was very excited. After looking up my flight on a map, I had the notion to ask him if I could use Japan as a stopover to visit Hong Kong and Singapore, too. He said, “Oh, that’s a good idea. We also have an office in Singapore.” He made all the introductions.

This first trip to Asia opened up a lot of doors for me. I was very anxious to please them and I’d learned my lesson about trust. It started a 27-year relationship, with me becoming the American face of their Japanese company. Even after that company was sold and our formal ties ended, I continued relationships with the key people who went to different places.

E+: It sounds like this one meeting with a Japanese toy guy really transformed your career.

Fuhrer: Definitely. Because I had this big company behind me, I was able to have accelerated meetings and more advanced entrée to places like Hasbro than a regular young guy just starting out. It put me on the map with the game-inventing community.

E+: I gather there are lots of categories in toy invention. What are some of the key ones?

Fuhrer: The toy industry is so vast. Let’s just talk about the category of “games.” Even within games, there are board games, word games, card games, skill-in-action games, balancing games… there are 15 different subsets.

I started out doing tabletop skill-in-action games, like Crocodile Dentist. Crocodile Dentist has now been on the market since 1990. I joke that that crocodile bought my house in Chappaqua. It’s been copied almost more than any other game; I’ve seen a copy of it at every flea market I’ve been to in the world.

WATCH THE VIDEO

A funny recent video of a toy reviewer and his kid playing Crocodile Dentist — 27 years after it first came out!

Another big hit of ours was originally supposed to be a Crocodile Dentist spinoff, but it became its own thing, called Gator Golf, another skill-in-action game, this one floor not tabletop. That led to Bongo Kongo and Rattle Me Bones—if you had kids in the ’90s, you knew these games.

[Visit the Nextoy site to see the company’s full impressive Product Gallery.]E+: What was your role in developing all these hits?

Fuhrer: A Hollywood friend of mine told me, “You’re a producer!” A movie producer puts together an actor, a script, the financing, the studio, the whole package. In my case, I will find the factory, the engineer, the industrial designer, the graphic artist for the packaging, the toy company customer, and more. As a one-stop-shop, Nextoy was a pioneer in the industry.

I also become a judge of the products, a screener, because there are vast cultural differences between the Asian resources and what sells in the U.S. — styling and taste and characters, in gameplay.

For instance, in Japan, they loved what we call “watch me” toys — a toy that has a really interesting mechanism and you just watched it flip over 10 times or something. Nobody in America wanted that. They wanted interactive and I had to figure out how to work with the Japanese to make that.

E+: Did Nextoy have a particular toy or game specialty?

Fuhrer: Nextoy ended up with a reputation of being very well connected in Japan and doing mechanical engineering–intensive projects, which separated us out because a lot of people do board games, for instance. Those are made out of cardboard and there’s a very low barrier of entry in that kind of game invention. Let’s face it: Everybody has a board game idea, especially schoolteachers. But it’s very hard to sell something where there’s this low barrier of entry.

E+: What was the common thread of all the games you developed since there are so many different types?

Fuhrer: My first thought is: “my taste.” But on second thought — and I don’t know if it was deliberate or not — the things that we brought to market over time seem to match my kids’ ages a bit.

And now I work on a lot of things for adults in their 20s and 30s, my kids’ ages again. It was definitely not intentional like that. Maybe the answer is, “it’s what I knew.”

E+: What can make a game a hit product?

Fuhrer: Luck, maybe? I don’t know. I have a gigantic closet of failed things that I thought would be great. I mean a very, very tiny percent of things actually hit the market, and even tinier stay. I don’t think I’d be exaggerating to say we’ve brought over 200 products to the market over 40 years of doing it. Maybe 10 of them still earn some royalty checks.

Fuhrer shared this favorite cartoon, which he said sums up the business side of toy invention.

E+: Because of the internet, are you seeing a surge of grassroots games coming out?

Fuhrer: Do you know the term “the “long tail?” That’s what’s going on today.

In the old days, if a game wasn’t by Milton Bradley or Parker Brothers, goodbye. Those kinds of companies, the kind I deal with, are mass market. They need to put up a television commercial and the toy has to look exciting and fun, and so on. An inventor like me had to come up with a toy that has to be safe, has costs to manufacture, and you have to figure out how many orders might come, etc.

With digital games, they don’t need engineering and tooling and so on. For example, one of the categories that was never really exploited by the toy companies were deep strategy games—the civilization games and Sims and all those niche games, almost like cults. I’m not one of those guys, but I know plenty of them and they build these worlds with huge amounts of depth.

The big game companies would wonder, How do you reach those customers? And how do you get the point across what the game is?

Well, those world-builders go on Kickstarter, or through the internet, they find like-minded people, a whole world of fans who will back the game.

E+: Besides deep strategy games, what else has become a big hit off the internet?

Fuhrer: One of the biggest successes in the history of games came off the internet a few years ago. It was the game that smacks you in the face, called Pie Face. I think originally it was a grandfather playing with his kid and they had shaving cream or pie custard or whatever it was. The grandfather put his head into this frame and then–Pie Face! Their video got many millions of views. Hasbro saw that internet video and commercialized it. In one year, Pie Face sold so many units that it blew past, like, the last 20 years of Monopoly!

WATCH THE VIDEO: PIE FACE

Then there was another grassroots challenge game featuring a dental guard mouthpiece as dentists use. The guard kept your mouth open and you had to read cards and other people would try to guess what you were saying. It turned into a big hit game. So now Hasbro and the other big toy companies keep looking at Kickstarter and they go on the internet to see what the heck is trending.

E+: Sounds like people are coming up with some crazy ideas online. I guess the secret is how viral and shareable these ideas are.

Fuhrer: Everybody is always trying to plan for a viral product. But I don’t think it’s plannable. It just kind of happens.

The big one right now is Wordle. Josh Wardle originally created it for his partner. She liked word games and he had been working on it for some number of years. He originally used the entire library of all five-letter words. When he tested it on his friends, there were so many obscure words it had no retention value. They would just give up, so he didn’t have many players. Eventually, he handpicked the words for the game, maybe only 20% of all the available five-letter words, and that had much more appeal.

But the big Wordle breakthrough, in my opinion, is something he got along the way from some users. They made the suggestion to make the puzzle results easily shareable with friends. And that made it a hit.

The funny thing to me about Wordle is if I were a toy company coming out with it, the name of the game would have to have five letters. It just would.

E+: You must have people buttonhole you all the time about their own game ideas. If they have an idea, what do you advise them?

Fuhrer: One of the first questions we ask is Is it original? And how do they know that it’s original? Is there a way to get any kind of intellectual property? Patents are important now. If I’m going to license something to Mattel and they pay me a royalty, and it comes out and Hasbro can do the exact same thing without paying the royalty, well, it’s just common sense to have a patent.

I would also stay away from things that have a low barrier of entry, like board games. If you want to sell a board game to a big company, you better establish it on your own first and have great success. Be able to say, Target or Walmart sold 100,000 of these. There has to be a history, otherwise, there’s no real interest in board games. We call them “progression games”—they use dice or a spinner and you march around the board, you collect things… There’s no market for that as an invention, so just enjoy it for yourself.

[See more toy-development tips from Robert on Nextoy’s Inventor Info page.]E+: Did you see anything change in game-playing during the pandemic when everyone was stuck at home?

Fuhrer: I think there was a tremendous amount more game playing. My related business is the KenKen puzzle business. We can’t monitor paper and pencil playing, of course. But KenKen is mostly a digital product, and we saw a dramatic growth because I think a lot more people had more downtime at home. Instead of spending their time driving or walking to work, now they’re in front of a computer where the game is just waiting for them.

Speaking of puzzles, the significant distinction between a digital puzzle and a game—like Candy Crush or Bejeweled—is that games are very transient. Puzzles become daily habits. You’ll talk to somebody who’s 80 years old and they’ve been doing the New York Times crossword puzzle for 50 or 60 years without missing a day.

E+: You mentioned KenKen, which is now a puzzle phenomenon complete with worldwide tournaments. How did you get involved with it?

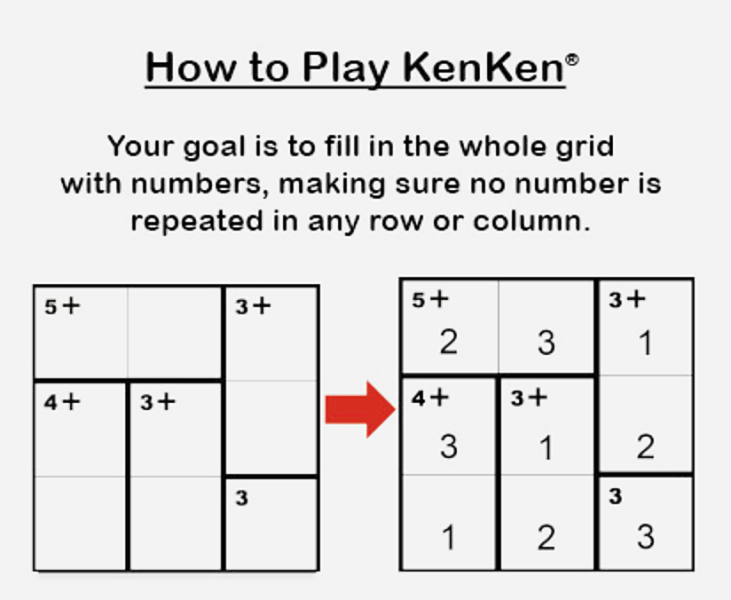

Fuhrer: KenKen is a grid-based numerical puzzle that was developed by a Japanese math teacher, Tetsuya Miyamoto, a guy who had no commercial ambition for it, actually. He was doing a weekend school, 3rd through 6th grade, and he came to feel that too much learning was based on memorization. He wants kids to learn how to think. He created the game of KenKen with that goal, and not too long afterward his students started winning the Math Olympics in Japan.

Visit the official KenKen Puzzle site to sample some puzzles.

The Ministry of Education in Japan at that time was looking for new innovative teaching methods. Somehow, they found Mr. Miyamoto and they got permission to go into his classroom and create a 40-minute nationally televised feature on the way he taught. Soon after, a giant book publisher in Japan published the first KenKen book. By April 2007 they had sold 3.5 million books, which is an enormous number for Japan.

When I showed up in Japan that year I saw the TV show they’d made about this math-and-logic game and called up the teacher for a chat. Then I was lucky: My Japanese business colleagues didn’t know how to market the book outside of Japan. They said, “Can you help us? We have this great game and it doesn’t use language, it’s numbers-based. We think it’ll work outside Japan.” They showed it to me and my eyes glazed over. I was like, This looks way too hard for the American audience, or something else brilliant about why it wouldn’t work. They basically forced it on me.

So, I said to them, “You know, this could be the greatest game in the world, but if nobody knows what it is it doesn’t matter.” They asked me how people might discover it and I said, “Well, it has to be in the newspaper like the crossword.” They said, “Bob-san, please put it in the newspaper,” which seemed ridiculous.

E+: It didn’t turn out to be that ridiculous because it eventually appeared in the New York Times. How’d that happen?

Fuhrer: I live in Chappaqua and I knew that the New York Times puzzlemaster Will Shortz lived nearby. [Related: See the recent Examiner+ Q&A with Shortz.] I didn’t know him, but I knew people who did. So, I said to the Japanese, “All right, give me some books. I think I can show it to the New York Times.”

When I got back, I contacted Will. He didn’t know me from a hole in the wall but I convinced him to let me see him. I thought I’d be going down to the New York Times but he said, “I’m just down the road in Pleasantville; come over at 11 o’clock Tuesday.” I showed up and he was in shorts and a T-shirt or something, very different than anything I’d envisioned.

I showed him the Japanese KenKen book, and said, “Let me try to explain who I am and how this puzzle works…” Well, he didn’t want to hear any of that. He said, “If you have to explain it to me if I can’t figure it out on my own, it’s a nonstarter. Just leave the book.” So I was out of there in 10 minutes. I figured, Well, that’s that.

Then several days later I was surprised to get an email from Will saying, “This is one of the most amazing puzzles I’ve ever seen! The book had 105 puzzles and I solved 103 of them. The last two were just a little too hard for me, but I’ll get to them. Before you do anything else, let’s have another conversation.”

And that’s how I brought KenKen to the U.S. It took more than a year before the New York Times picked it up, but KenKen did become a phenomenon here in the U.S. and around the world, showing up in a lot of publications now and with tournaments in many countries.

For more about the KenKen phenomenon:

Take a look at this 1-hour New Yorker documentary on KenKen

Read Will Shortz’s 2019 essay about KenKen upon its 10th anniversary of appearing in the New York Times.

E+: With huge hits like Wordle and KenKen, it sounds like puzzle games are having a moment.

Fuhrer: You know, the New York Times actually beefed up their puzzle-game offerings the last couple of years and they don’t do that without a lot of study and analysis. Maybe they figured out that people can get the news anywhere, but good-quality daily puzzles are rare. And, as I mentioned previously, really habit-forming.

E+: Is there anything about Westchester or Chappaqua that made your career as a game maker more interesting or possible?

Fuhrer: The luck of me living so near a puzzlemaster like Will Shortz was big. He and I have become friends and I think he is a treasure.

E+: I hear you’re now getting ready to sell your Chappaqua house and move down to your Florida condo, maybe keeping a smaller place up north. That must be a big change after all these years.

Fuhrer: Yeah, knowing we were going to be packing up has been stressful. Because remember that gigantic closet I mentioned earlier? I’ve kept every fax, email, document, and prototype of my toy career since 1981! I have all the back-and-forth of how my products got developed—the successes and the failures. What was I going to do with all this stuff?

I mentioned my quandary to a retired friend from the toy industry, and he said, “Well, why don’t you give the toy museum a call?” That turned out to be a great idea. I started the conversation by sending the Strong National Museum of Play [based in Rochester, New York] a photo of one of my most treasured pieces of art—a 7 foot x 4 foot wooden map of the USA with each state featuring a different toy related to that state (for instance, Ohio shows the Etch-A-Sketch, originally made by Ohio Art). I commissioned it in 1991 from my artist friend Peter Buchman; at the time he was making a lot of maps with varying themes. It features some of my toys from that era such as Crocodile Dentist, Gator Golf, and the Batcycle.

“Toy Map,” an artwork created in 1991 as a collaboration between Robert Fuhrer and his friend, artist Peter Buchman, will hang in the Strong Museum’s new History of Toys wing.

Well, the Strong curators were excited about that map and even more excited when I told them about all of my other stuff—because the museum is used a lot for research and all my faxes and documents capture the toy and game development correspondence between me and the Japanese and me and the American toy companies. It really brings alive a time when things got made very differently from today’s computer-aided design.

In April, the president of the museum and his head of communications were in Chappaqua for two nights checking out everything, and eventually, a large van left my house carrying 40 years of my archives, artwork, some prototypes, etc. We’ll see what they do with all that. But I do know that the wooden toy map is going to be permanently exhibited in the Strong’s new History of Toys wing — installed up high enough so nobody can touch it.

E+: So, Robert, after nearly 50 years in the toy industry are you slowing down a bit?

Fuhrer: Well, I’m not retired — we had a big hit with Spirograph Animator just last year—but things are changing around here. Both of my two sons have become active in the business, one more than the other. And you know, with Covid, things changed… The toy industry, especially on the inventor side, which I’m on, is actually a very tight fraternity and there’s a lot of social aspects to it, a lot of in-person deal-making and conversation. That’s definitely been compromised the last couple of years. I just can’t imagine if I had to start my business today and have to deal with this way of making contacts. You can’t really share drinks or network over Zoom.

WATCH THE VIDEO

30-second cute Spirograph Animator video ad

E+: This last question is a good one for you because of all the travel and collaboration you’ve done with people from different countries. Can games play a role in bringing together our fractured world?

Fuhrer: The inventor of KenKen says with a straight face that KenKen leads to world peace. The reason he says this is because it’s language-free, it’s gender-free, it’s age-free, and people can collaborate with and play against people in every nation of the world.

It’s a human trait to play. Around the world, we all play, even though there are cultural differences, as I mentioned before. Many games transcend cultures, though. When you have all these worldwide games like chess, backgammon, Go, Sudoku, and mahjong, you have something that is bringing our world together, every day.

Laura E. Kelly is a Westchester freelance writer, editor, and designer specializing in profiles of local people, organizations, and events. She owns an editorial & digital-branding business in Mt. Kisco and can be reached at laura@laura-e-kelly.com.

We hope you’ve enjoyed today’s section of Examiner+. What did you think? We love honest feedback. Tell us: examinerplus@theexaminernews.com

For hyperlocal news coverage of Westchester and Putnam from our four community newspapers, visit our sister site, www.theexaminernews.com

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.