Winning the War of Ideas on the Afghan Battlefield

News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

A Scarsdale lawyer teamed with an Iraqi refugee and an immigrant from Singapore to create a non-profit that brings liberal ideas to the Arab world. Their next mission: Afghanistan

Good morning! Today is Friday, November 5, and you are reading today’s section of Examiner+, a digital newsmagazine serving Westchester, Putnam, and the surrounding Hudson Valley.

Need to subscribe — or upgrade your Examiner+ subscription to enjoy full access to all of our premium digital content? Details here.

IBB founder and president Faisal Saeed Al Mutar (Photo: IBB)

Two months after the final American troops left Afghanistan, the media and much of America have moved on. The initial wave of intensive coverage has long since abated, even as the threat to the thousands of Afghans still trapped in Afghanistan who worked with American troops remains.

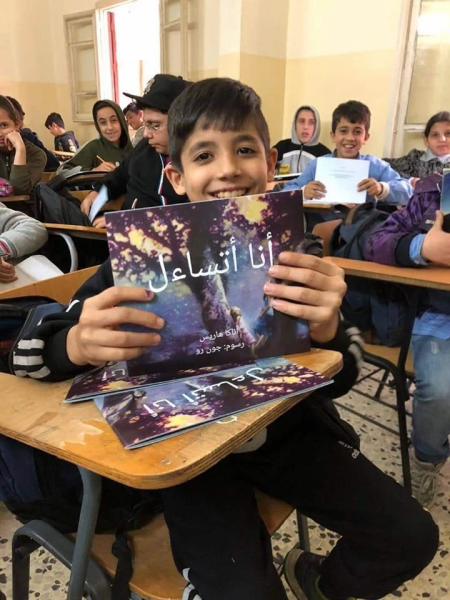

But as American forces left the country, New York-based non-profit Ideas Beyond Borders has stepped in to support the Afghans left behind. IBB, an anti-extremism organization focused primarily on translating books and articles from English into Arabic, has dramatically scaled up its operations in Afghanistan. It is now translating works into Dari and Pashto and helping Afghans who worked with Americans escape, with an eye towards supporting women’s education in the country.

The organization has hired more than 60 editors, publishers, and proofreaders in Afghanistan to provide translation and other services, and plans to hire more in the future. The translators began their work last month and have already translated more than 160 articles. “These are the people who were left behind by the US withdrawal. They are the ones that are joining our team,” Faisal Saeed Al Mutar, the president and founder of IBB, says. “They support a lot of the values that many Americans support.”

Al Mutar launched Ideas Beyond Borders in 2017 with Melissa Chen, a journalist and an immigrant from Singapore. The organization, which relies on private donors to fund its $1.8 million in annual spending, runs several initiatives. Its flagship program, called House of Wisdom 2.0, employs some 120 translators and has translated 20 books and more than 22,000 articles into Arabic, as well as hundreds into Kurdish and Farsi.

“I’ve read that more books are translated into Spanish in a given year than into Arabic in the last 1,000 years. It really has been a desert for outside thought for so long.”

IBB’s board includes Steven Pinker, a Canadian psychologist once named one of Time’s most influential people in the world, and former Reason editor-in-chief Nick Gillespie. The board chairman is Scarsdale resident Sam Hershey, a restructuring litigator at White & Case.

IBB Board Chairman Sam Hershey (Courtesy White & Case)

The Opposite of Vegas

An Iraqi refugee, Al Mutar understands the importance of both combating extremism and promoting free thought in the Middle East. Now 30, he grew up under the rule of Saddam Hussein and saw his reality shaped by the dictator’s regime-run media.

“All of the information, and I mean all of it, was controlled by the state,” he recalls. “The punishment for acquiring information outside of the country, through satellite television or radio, was either jail or death.”

The climate following Saddam’s removal was not much better; Al Mutar says the country went “from 1984 to Brave New World,” from controlled truth to forced truth.

“We moved to where there are 1,000 newspapers and there is a lot of content but very little factual content,” he explains.

Neither was conducive to an informed citizenry; until 2005, Al Mutar believed that Iraq had fought off 35 invading countries to emerge victorious in the first Gulf War.

“That is why I became very interested both in the spread of ideas but also in advancing critical thinking skills,” he says.

Al Mutar often says that the Middle East is the opposite of Las Vegas – what happens there does not stay there. Twenty years ago, while Al Mutar was still living under Saddam’s Baathist regime, 285 million Americans came to this realization when United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center. Hershey, a freshman in college at the time, says the September 11 attacks had a major impact on him.

“It came as a total shock and opened my eyes to an aspect of foreign policy that I’d been just blithely ignorant of for so long,” Hershey, now 38, remembers. “Suddenly, it was extremely important to me on a personal level.”

Hershey wanted to understand not just the region but what conditions could lead to such a clash of civilizations. He began reading books by Christopher Hitchens and Sam Harris, whose 2004 bestseller The End of Faith addresses the conflict between religious faith and rational thought. By around 2015, he began watching videos of Al Mutar, who provided summaries of local news stories to Hitchens when the latter visited Iraq following the fall of Saddam’s regime.

Al Mutar had gotten out of Iraq in 2009 and, after living in Lebanon and Malaysia, came to the US as a refugee in 2013. He and Chen decided to launch Ideas Beyond Borders in 2016. Looking to incorporate as a 501c3 nonprofit, Chen posted on Facebook seeking a lawyer to help them get off the ground. Hershey, then an associate at Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton, had never met either Chen or Al Mutar but responded to her post. The three met for lunch at The Dutch, a popular SoHo bar and grill, and Hershey’s firm was soon on board as pro bono counsel.

He later became chairman of the board, overseeing the implementation of IBB’s programs while Al Mutar and Chen run the operation. He remained counsel when he left Cleary Gottlieb for White & Case. The two firms have provided hundreds of thousands of dollars in pro-bono services, Hershey says.

Al Mutar votes in the 2010 Iraqi elections near the Iraqi embassy in Beirut.

With its House of Wisdom 2.0 initiative, Al Mutar recalls a more tolerant time in the Middle East — the original House of Wisdom was an intellectual center in Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate in the 7th century AD.

“There are eras in which Baghdad and other places [in the Middle East] used to have atheists, and they used to be prominent advisors to the Caliph,” he says.

One focus of this initiative has been translating Wikipedia articles. Less than one percent of the articles on Wikipedia in English are also in Arabic, according to Hershey. Working with translators across the region, IBB has also translated nearly two dozen influential books, with a focus on works that promote pluralistic values and rational thought like Pinker’s Enlightenment Now, Ayn Rand’s Anthem, and Bari Weiss’ How to Fight Anti-Semitism.

Listen to Momen, an IBB translator who speaks of his experiences in Mosul

“It is really amazing to me the void that we are filling, and that it’s been a void for so long,” Hershey says. “I’ve read that more books are translated into Spanish in a given year than into Arabic in the last 1,000 years. It really has been a desert for outside thought for so long.”

IBB has expanded beyond text translation and produced some 120 Arabic-language videos, similar to Vox Explainers, on topics ranging from why people believe conspiracy theories to how to stop the spread of Covid-19. They also launched a campaign to stop the spread of Covid misinformation.

Aside from translations, IBB runs a microgrant program called Innovation Hub that provides funding to initiatives throughout the region to promote human rights and democracy-building. The hub has backed initiatives ranging from a plan to build libraries and establish literary programs for former slaves in Mauritania, the last country in the world to ban slavery, to a heavy metal band in Iraq, called Dead Tears, that sings about fighting extremism.

“One of the main challenges that these groups have throughout the region is that, to put it simply, they don’t know how to write a grant proposal,” Al Mutar says. “They don’t know how to match the language of international development and all of the buzzwords and the lingo necessary to make it happen.”

Another project has been the rebuilding of the University of Mosul Library, which was destroyed by ISIS. IBB provided 5,000 books and twenty computers and printers, part of a $200,000 renovation.

The library at the University of Mosul in Iraq, once among the finest in the Middle East, had a million books — about 600,000 were in English and the rest were in Arabic and other languages. In 2015, ISIS embarked on a book-burning campaign throughout the Anbar province, laying waste to the University’s collection. (IBB)

This year, IBB donated more than 5,000 books and twenty computers and printers to help restore the central library of the University of Mosul in Iraq that was destroyed by ISIS. (IBB)

Today, children of all ages learn and enjoy from the restored university library. (IBB)

Operating in the Graveyard of Empires

It’s been more than a decade since Osama bin Laden was tracked down and killed in his Abbottabad compound, and Americans had since tired of the war in Afghanistan and favored withdrawal. At least that is what polls said, after years of political candidates from both parties lamenting the endless war and promising to bring it to a close.

But that was before scenes of teenagers clinging to the wheels of departing airplanes, mothers tossing their babies over barbed wire, and seas of desperate Afghans surrounding Hamid Karzai International Airport filled TV screens and entered the collective consciousness. And before the Taliban, viewed for a generation as a caricature of evil cast into the dustbin of history, re-emerged to dispatch a humiliated former superpower with shocking ease.

While most Americans viewed these scenes with feelings of horror and helplessness, Al Mutar saw that he and his organization had a role to play. In the near term, that meant helping Afghans trying to flee the country.

“As a refugee myself and as someone who has a very good knowledge of the region, and at the same time has a connection to a lot of people in Afghanistan, most of the work that I’ve been doing has been providing logistical support,” Al Mutar says. “I was providing significant advice on what the major airports are, how people can get out of the airports, what cities they can go to, and which countries give visas.”

Al Mutar and Chen have been part of what’s been called alternately a “Digital Dunkirk” and an “Underground Railroad” to save Afghans from the seventh-century theocrats now in power (Chen’s remarkable account of such efforts was published in detail by former New York Times editor Bari Weiss). In addition to handling logistics, IBB has also raised funds to support these missions. Al Mutar was recently in Turkey in an effort to understand the situation on the ground, and plans to travel to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan next year to help rescue translators still trapped in Afghanistan.

But as many Afghans as Chen, Al Mutar, and scores of other activists and former US servicemembers may be able to save, close to 40 million men and women will have to live under Taliban rule for the foreseeable future. And IBB is looking to support them as well.

The expansion of House of Wisdom 2.0 into the Afghan languages – giving Afghans access to the ideas that will eventually bring down the Taliban – is a part of that. This does not just mean translating works, but making sure Taliban subjects can access them.

“At this moment, as we are doing this interview, the Taliban has not shut down the internet,” Al Mutar says (as of press time it’s still true, for the most part). “However, we are training those translators with circumventing tools.”

IBB uses a number of methods – virtual private networks, encryption tools, mirroring – to both ensure their site can be viewed and their translators remain anonymous.

IBB also plans to double its grant funding and include Afghanistan. Al Mutar is focused on supporting women and girls, especially those looking to continue their education.

“We want to make sure people in Afghanistan remain connected to the world,” he says.

“One of the conversations that I am having right now is with educational organizations across the world who can actually provide education to the girls who are banned from going to school,” Al Mutar says.

At the moment, things look bleak for both women and liberal values in Afghanistan. But Al Mutar takes the long view. He points to protests against the Taliban led by women demanding their rights.

“What we are focused on is making these ideas mainstream, making these ideas localized and really adapted to the local population so that they become the fighters for these values,” he says. “If people get exposed to these ideas, and if we fund initiatives that support these ideas, these ideas will be instilled in the local population.”

Andrew Vitelli is the former editor of The Putnam Examiner and The White Plains Examiner. A Hastings-on-Hudson native, he now lives in White Plains with his wife, Zeynep, two-year-old daughter, Zoe, and their dog Beasley.

We hope you’ve enjoyed today’s section of Examiner+. We love honest feedback. Tell us what you think: examinerplus@theexaminernews.com

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.