‘Time to Talk and Tell My Story’: Holocaust Survivor Shares his Story with Local Students

News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

By Elaine Clarke

It’s 1943, and Fred Schoenfeld, a little boy of just about seven years old, must flee his Czechoslovakian hometown to hide in his father’s warehouse from the murderous Nazi regime. The family eventually escaped to the mountains of Slovakia, where they survived the final six months of the war.

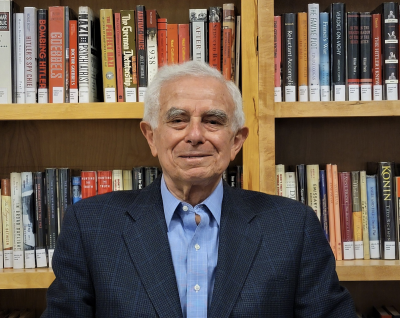

About eight decades later and across the Atlantic, the same Fred Schoenfeld stands before a group of local high school students, sharing his harrowing story with today’s youth – many of whom are growing up in a world where Holocaust survivors are rapidly dwindling and the weight of this recent history feels increasingly distant.

Schoenfeld spoke to sophomores yesterday, May 28, at Walter Panas High School about his experience under Nazi rule. The event was organized by English teacher Meghan Vingo through the White Plains-based Holocaust and Human Rights Education Center (HHREC).

“I’m a Holocaust survivor,” Shoenfeld said in an interview with The Examiner before the talk. “I never considered myself as one, because I was fortunate enough not to go to concentration camps.”

But at the urging of his two sons, Shoenfeld began sharing his story. They reminded him of his history, emphasizing that he was a survivor.

“They kept telling me, ‘Listen, you were there during the Holocaust. You’re here today. That means that you survived the Holocaust,’” Shoenfeld explained.

A Time to Talk

Around the same time, Shoenfeld recalled, books were being published denying the Holocaust’s very existence. That disturbing trend added fuel to his desire to bear witness, trying to ensure the truth be told loud and clear. His own grandfather was deported to Auschwitz in 1942 and became one of the six million Jewish people slaughtered by Hitler’s Nazi forces.

“With every passing day, there are less and less survivors able to speak,” Shoenfeld said. “So I decided it was time to talk and tell my story.”

When teaching about the Holocaust last year, Vingo realized that students did not have a significant understanding of the genocide.

“My students were really interested in learning more, and they asked me if there were any survivors left,” said Vingo, who grew up in Ardsley and now resides in Putnam County. “Growing up in Southern Westchester, I had many experiences with Holocaust survivors coming and speaking at my school.”

Looking for someone who could speak to the students, she was then led to the HHREC.

The nonprofit organization supports teachers and students in meeting New York State’s mandate to include the Holocaust and other human rights violations in the curriculum. Founded in 1990, HHREC not only offers educational programs but also works to preserve and honor the stories of Holocaust victims.

“Our endeavor is to teach about the Holocaust, and so we have a number of different methods to do that,” HHREC Executive Director Millie Jasper said.

In 1994, after New York State passed legislation requiring schools to teach about the Holocaust, slavery, and other human rights abuses, the organization expanded its education and training programs to better assist teachers.

“Bringing in a Holocaust survivor with first person testimony is vital for the students,” Jasper said. “We’re very happy when the schools call us to bring someone in.”

Shoenfeld, for his part, has also spoken about his family’s escape from the Nazis in higher education institutions, including at Clark University. He stresses that while the Holocaust is often remembered for the six million Jewish victims, it also targeted many other groups.

“I make sure that I tell them that, yes, it’s the Holocaust. It was 6 million Jews who passed away, but at the same time, it’s not [as well] known that other people went along with them,” Shoenfeld said. “If you were gay – all the gay community was sent to concentration camps – [the Romani], the physically disabled.”

Schoenfeld also knows firsthand that changing attitudes is a challenging and slow process.

In 1998, Schoenfeld and his family returned to their hometown in Slovakia and witnessed that antisemitism had far from disappeared.

And in today’s divided world, he notes that ignorance leads to history repeating itself – a particularly alarming prospect, he said, amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the troubling rise of anti-semitism in the United States – an urgent message he consistently emphasizes in his speeches.

“Yes, there are no concentration camps, no gas chambers at this time, but all over the world, somebody’s treating different minorities the same way,” Shoenfeld said. “They should remember what had happened and be good citizens and fight for what’s right to see that it never happens again.”

Living History

As for Vingo, she hopes the presentation will inspire her students to think more critically about the world and become upstanders – leading with empathy and an open heart.

“I always tell my students that they should question everything, even me,” Vingo said.

She also stressed the idea of building bridges between our differences.

“I was in high school when 9/11 happened and I vividly remember not knowing much about Islam or the Middle East,” Vingo recalled. “It made me want to learn more about that, and the more I learned, the more I understood. For us to really be the United States of America, we have to understand how our differences really unite us.”

Schoenfeld hoped to remind the local sophomores, remembering the past is a responsibility that grows more urgent with time.

“I want many people to know the story of the Holocaust, because very soon, there will be no Holocaust survivors left to tell the story in person,” Schoenfeld said. “So it’s up to the present generations to remember and to make sure that it doesn’t happen again.”

In fact, his message seemed to get through. Asked to reflect in writing on what they took away from the presentation, many students offered thoughtful answers.

“Don’t look away from history,” Campbell Eaton said, “because it could happen in your life.”

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.