SPECIAL INVESTIGATION: Job Program Fails Disabled Locals

Investigative / Enterprise In-depth examination of a single subject requiring extensive research and resources.

Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

Our Special Report Shows How Area People in Need ‘Fall Off a Cliff’ After High School

This is the second installment in a continuing series about issues impacting local people with disabilities, and the need for improvement.

By Adam Stone

Maddie Diorio, a vivacious and creative 18-year-old Fox Lane senior, maintains a keen interest in the world of fashion.

Eager to gain experience in the workforce, she was excited last year to enter ACCES-VR, a state program designed to assist people with disabilities gain employment and career support.

ACCES-VR, which is short for Adult Career and Continuing Education Services-Vocational Rehabilitation, appeared to be perfectly suited to help Maddie. She figured she’d maybe score a job working retail at a Mount Kisco clothing store.

“She’s like, ‘If I get a Gap discount, I get it for everybody,’” her mother, Holly Diorio, recalled with a light chuckle in a telephone interview last week.

But Maddie’s excitement quickly soured as her journey through the program was fraught with communication breakdowns and inaction, failing to deliver her an appropriate job either last year or this year.

“The last thing I was told this time last year was that they were going to place me at T.J. Maxx, and I never heard from them again,” Maddie explained in a separate phone interview last Tuesday.

Maddie was left in the dark, never receiving any further communication about the opportunity from ACCES-VR, a program also designed to provide support through training, education, rehabilitation, and long-term career development.

“We were told it was going to be a very supportive experience, and it has been the most non-communicative, irresponsible experience I have ever had,” Holly Diorio bemoaned. “I just don’t understand how they can make the promises they do and not follow through. It’s incredibly frustrating and disappointing.”

Holly, her husband Ken, and Maddie are far from alone in their frustration. (Full disclosure: The Diorios are friends, and, separately, I have a nephew in the program.)

Maddie’s case is part of a larger pattern of failure within our local office of ACCES-VR, a program run through the state Education Department (SED), an Examiner investigation reveals.

During interviews with parents and program participants, as well as recorded conversations between families and ACCES-VR, a consistent narrative emerged, with story after story of the program’s communication and execution flops.

Some key conclusions and revelations:

- Three hundred counselors serve 50,000 people across New York State, and a full third of the 300 are eligible for retirement right now.

- There are only 14 vocational rehabilitation counselors in the White Plains office; they manage an average caseload of 198 clients, according to the New York State Education Department. But The Examiner learned of counselors with caseloads exceeding 300.

- In addition, senior staff maintain additional caseloads. Counselors and senior staff currently handle a combined 3,099 cases.

- A rash of retirements have led to staffing complications.

- Understandably overwhelmed local counselors, despite their best efforts, sometimes appear to embrace a “checkbox mentality” of securing disabled people with ill-fitting jobs instead of helping to nurture their careers.

- Nonprofit, private and non-government agencies, which help deliver services for disability programs, require more funding to account for cost-of-living increases not currently accounted for in their state aid.

- The program places excessive demands on developmentally disabled people who struggle with executive functioning, which is the ability to plan, organize, and manage tasks. This leaves them ill-equipped to advocate for themselves when communication breaks down.

- The case overload issue is exacerbated by some non-deserving recipients gaining access to the program.

- Fundamental problems are largely the result of bureaucratic inefficiencies and benign neglect, not indifference to disabled people. The status quo currently permits a lack of excellence in execution.

- Disability services running through the Education Department creates systemic barriers to enhancement. Some reformers believe programs should operate through the Labor Department, or via a new standalone agency.

- Structural challenges, such as a dearth of qualified counselors, make it legitimately difficult for the state to hire the needed volume of qualified counselors, an issue that department officials are trying to address.

Old Issues

The problems are also nothing new.

“I did not have much luck with ACCES-VR with my son,” said Ann Chiappetta, a blind New Rochelle resident I also happened to feature last week when reporting about web accessibility for the disabled in part 1 of this series. “It was over 10 years ago but I found the placement person did not take into account my son’s social anxiety and kept pushing him toward positions wherein he was exposed to dealing with the public at large.”

Some people I spoke with preferred not to provide their names. One northern Westchester mother of a developmentally disabled son said the program “lost the original application.”

“(I) then reapplied and had to call 100 times to get the ball rolling,” she said for effect, later clarifying she called precisely six times before generating a response.

Once she established contact, she said the “lady was rude.” In fact, it was only a result of the area mother’s proactive involvement in the effort, reaching out to local businesses herself, that her son secured employment for the coming summer, technically via ACCES-VR.

I was also able to review recordings, including a conversation from just last week, between ACCES-VR counselors and local families.

One family was struggling to achieve results through an agency the state uses to deliver on ACCES-VR services. The counselor was clearly trying to be helpful in the recorded conversation, acknowledging the importance of the nonprofit agency, Ability Beyond, to be more communicative. She said she hoped that in the future, the student would alert her to when communication breaks down.

However, the parent on the recorded phone call suggested that putting the onus on her young adult daughter, who struggles with executive functioning and hasn’t yet graduated high school, applies excessive responsibility and pressure on the person the program is designed to serve.

“To be honest with you, I have 300 cases,” lamented the counselor, appearing sympathetic and exasperated at the troubled bureaucracy she herself must navigate.

It was also pretty dispiriting to review some of the e-mails the young adults sent to the program, seeking contact.

“Sorry for the late response but I would be able to meet on Friday at 5 pm? Let me know if that works for you,” reads a May 18 e-mail to Maddie Diorio from her assigned employment specialist.

“Friday at 5 works,” Maddie replied the next evening, but that’s where the conversation apparently stalled, before Holly and Ken nudged again themselves in recent days.

The shortcomings haven’t gone unnoticed by state officials.

Performance Review

Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli audited ACCES-VR last year, and the investigation revealed a lack of timely eligibility determinations and a failure to adequately monitor the program’s effectiveness. There was a follow-up audit initiated just last month, I learned on Friday.

I asked DiNapoli’s deputy press secretary, Kristina Naplatarski, for any success stories or positive outcomes resulting from the audit report’s recommendations. But, in an e-mailed answer to questions, she said it is too early to call.

“The follow-up audit was just engaged last month, therefore, we do not know the implementation status of recommendations yet,” she replied, citing feedback she received from the audit team.

In a pretty stinging rebuke, Naplatarski indicated the office was taken aback by the lack of collective data related to performance achievement goals. Additionally, she said in her e-mail that the department did not meet the goals reported to the U.S. Department of Education’s Rehabilitation Services Administration, which could warrant further investigation into goal setting and reasons for non-achievement.

“You cannot evaluate the success of a program, if you do not collect and analyze performance data,” she told me in the e-mail, referencing the answers she received to my questions from the audit team.

Naplatarski did suggest some potential progress.

“The agency’s 180-day response noted some steps they were taking to address the recommendations,” she said.

The follow-up audit is primarily focused on assessing whether recommendations from last year’s audit have been implemented or not.

So, have they been implemented?

“We will be able to answer this once the follow-up has been completed,” Naplatarski told me.

The audit, released on March 30, 2022, includes a “key findings” section.

“The Department did not provide any documented evaluations to show it was adequately monitoring the ACCES-VR program,” it says. “Inadequate monitoring, incomplete IPEs, and delays in an already complex process can deter participants from gaining employment, which can further result in disruption to the participants’ goals of independent living and rising out of poverty.”

DiNapoli’s review references the incomplete nature of what are called Individualized Plans for Employment, or IPE.

The IPE is a written plan that lists employment goals, outlines the services ACCES-VR would provide and identifies steps to take to achieve the goals.

As for the audit recommendations, DiNapoli encouraged stronger oversight of the program.

In a March, 2022, press release, DiNapoli applauded the appointment of a chief disability officer, and said he hoped the hire would “result in much-needed improvements to the state’s services and support for people living with disabilities.”

“People with disabilities often face great obstacles in finding and keeping the jobs they want, and the pandemic has only made things harder,” DiNapoli said in the prepared statement. “The State Education Department needs to do a better job with this important program for people with disabilities. The program’s vital mission is not always fulfilled due to the agency’s failure to monitor progress and by significant delays in implementing the individual plans for achieving participants’ employment goals.”

“People with disabilities often face great obstacles in finding and keeping the jobs they want, and the pandemic has only made things harder,” DiNapoli said in the prepared statement. “The State Education Department needs to do a better job with this important program for people with disabilities. The program’s vital mission is not always fulfilled due to the agency’s failure to monitor progress and by significant delays in implementing the individual plans for achieving participants’ employment goals.”

(The state’s chief disability officer, Kimberly Hill, did not reply to my requests for comment.)

Unemployment rates for New Yorkers with disabilities are far higher than the general population, and the pandemic exacerbated this issue, DiNapoli noted in his report. Between September 2020 and August 2021, the average unemployment rate for people with disabilities was 15.2 percent, significantly higher than pre-pandemic levels.

The audit also says the ACCES-VR program struggled to meet deadlines for eligibility determinations, and with conducting annual reviews. Education Department officials don’t agree with much of the audit’s rebuke, the details of which can be read online.

Naplatarski did note for me how the mandated 180-day response from SED mentioned some steps it is taking to address recommendations.

“ACCES-VR’s implementation and continued use of weekly case status reports concerning timeliness in completing eligibility determinations and developing individualized Plans for Employment (IPE), addresses this recommendation,” Sharon Cates-Williams, executive deputy commissioner at SED, wrote to the comptroller’s office in a portion of the 180-day letter on Sept. 22, 2022, replying to one of the audit’s suggestions to enact improved controls.

Tools in the Toolkit

Assemblyman Chris Burdick (D-Bedford) sits on the People with Disabilities Committee.

He mentioned the possibility to me last week of scheduling a meeting with the local district office, to begin a due diligence process. The assemblyman also cited the possibility of a public hearing, if progress isn’t achieved. New legislation also always remains an option, if necessary.

In a telephone interview, Burdick acknowledged the need for reform within the system. He mentioned the importance of reviewing the program’s internal evaluation system and the ratio of counselors-to-disabled people in need of assistance.

Burdick stressed the need to connect capable people with suitable employers and ensure a proper match between skills and job opportunities.

“One of the phrases that’s used is, look as much at the person’s ability, not just disability,” the assemblyman observed. “I think one of the things that I hear a good deal about is, how do you go about trying to connect these very smart, capable people with employers that can utilize them? How do you match it up?”

He said he plans to immediately delve deeper into the issue, conducting further research, and intends to follow up on the comptroller’s audit.

I asked about the tools in his toolkit to produce fixes.

“You can ask for a meeting with head of ACCES-VR to say, ‘Okay, here’s this audit that’s come out,” the lawmaker said. “Tell us how you’ve addressed it. It’s been a year. How have you addressed it?’”

Staffing Woes

Staffing Woes

I was able to connect directly last week with SED, the facilitator of the program.

In an approximately 50-minute Zoom interview, Adult Career and Continuing Education Services Deputy Commissioner Ceylane Meyers-Ruff displayed deep thoughtfulness and a passion for helping disabled people. Her candor, command of the nuanced issues and acknowledgment of problems were all incredibly refreshing and impressive.

Because the ACCES-VR program aims to serve 50,000 people with 300 counselors, I pressed Meyers-Ruff repeatedly to share how many people she’d reasonably like to see added to the staffing ranks, in an ideal world.

“I would like to double that number if I could, but I want to be realistic,” she eventually replied near the end of the interview, referring to the current 300-counselor figure needing to be higher. “That’s why I don’t want to commit to a hard number. But if I could double the staff, I would absolutely do that.”

Meyers-Ruff did stress how the eye-popping ratio might be somewhat deceiving, since participants come in and out of the program, utilizing it when needed. It’s not a circumstance where there are 50,000 people with daily demands.

Money also isn’t a fundamental problem, she said. The program generally has access to the cash it needs through considerable federal government support to fund its desires. Problems lie within the difficulty of hiring qualified candidates, Meyers-Ruff observed. Also, of the 300 current counselors statewide, I learned a full third are eligible for retirement right now, presenting what sounds like a potentially crippling problem.

“There is an aging population in state government employment, and we’ve had a lot of counselors retire,” Meyers-Ruff said, citing what she noted was a national problem. “And then you add the layer of COVID, I think (that) accelerated retirement across the state. That being said, there’s a lot of initiatives that we’ve been putting in place to recruit more counselors.”

The organization does offer paid internships and has recently implemented a training program to facilitate the early onboarding of counselors.

Additionally, Meyers-Ruff pointed to an initiative, in partnership with the University of Buffalo, allowing staff members to pursue a master’s degree in vocational rehabilitation counseling, as mandated by federal requirements. She acknowledged that the availability of services may differ across the state, as some offices have a full complement of counselors while others do not.

As for our local area, it most definitely and unfortunately falls in the latter department.

“So the Hudson Valley area where White Plains is located, that is an area where we are lower on counselors,” Meyers-Ruff acknowledged. “However, as I said before, some of these newer initiatives that we are putting in place is really helping us identify more counselors. It’s actually a national issue, having sufficient counselors.”

Careers, Not Just Jobs

The program is doing plenty of successful work across the state.

ACCES-VR helps people with a diverse range of disabilities, including individuals with mental health diagnoses, physical disabilities, chronic health issues, deafness or hearing impairments, intellectual disabilities and alcohol or substance abuse disorders.

The program’s mission is not designed just as job placement; it’s intended to help people with disabilities establish career goals and provide the necessary long-term services to achieve those goals.

“I have to say that the staff do a really excellent job,” Meyers-Ruff said. “We have so many success stories of people who have received access to VR services and have accomplished their career goals.”

(The department initially said it could likely fulfill my request last week to speak to local disabled people who have benefited from services. But officials weren’t ultimately able to connect me with anyone to illustrate a positive case study review).

Regarding eligibility requirements, Meyers-Ruff says documentation is relatively straightforward.

Applicants are required to provide basic information such as name, date of birth, gender and racial or ethnic background. Proof of disability is also necessary, which can be provided by medical professionals or psychologists associated with the program. However, people who already receive Social Security disability or Medicaid benefits are automatically considered eligible.

Meyers-Ruff, in discussing the structural challenges, emphasized that the shortage of counselors is exacerbated by the reduced number of graduate programs offering vocational rehab counseling degrees and competition among state agencies and nonprofit organizations for qualified candidates.

I asked Meyers-Ruff about the alleged checkbox mentality, the prioritization of job placement over matching people with opportunities that align with their skills and aspirations.

“Yeah, so I would say that we were never a checkbox mentality,” she said. “What I would say, and again, I want to give the caveat that when you have over 300 counselors and you’re serving 50,000 people a year, clearly the goal is that everyone, no matter where you’re at in New York State, should be having the same exact experience. That being said, we’re dealing with humans and sometimes it is not a perfect scenario.”

She also said the office has actually gotten better over the past decade in utilizing qualitative data, not just quantitative, subsequent to the passage in 2014 of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. The WIOA was designed to help job seekers access employment, education, training and support services to succeed in the labor market and to match employers with the skilled workers they need.

In fact, getting employers to understand the value disabled people can bring to jobs, and remove the stigma, is a big piece of solving the larger puzzle.

“The other important piece of this is the work with employers, because we need businesses that are willing to hire people with disabilities,” Meyers-Ruff said.

I also wondered why the program places such an onus on young adults, some with executive functioning organizational issues, to advocate for themselves. Meyers-Ruff acknowledged the concern.

“At 18, our customers are legally old enough to make their own decision,” she said. “And so the case is in their name unless they give approval for us to be communicating with the parent. Sometimes we have situations where the customer and the parent are not on the same page.”

And what about all the communication snafus?

“If someone feels I’m not hearing from my counselor in a timely way or I don’t like the employment goal that’s been developed with my counselor, we have multiple mechanisms to work with that individual,” Meyers-Ruff said. “All they have to do, there’s an 800 number, there’s an e-mail that they can send, and that would trigger either a review of their case, maybe mediation if necessary, or (an) impartial hearing. And we encourage that.”

My message seeking comment from Gov. Kathy Hochul was not returned.

Falling Off a Cliff

Chappaqua’s Karen Bazik’s 23-year-old son, Hans Kibler, who is studying political science, was an honor student at Westchester Community College before recently transferring to Manhattanville. Trying to secure services from ACCES-VR since 2018 has been a fiasco.

A 2018 graduate of Irvington High School, after previously attending Chappaqua schools, Kibler is someone in need of support, as a person with autism, related anxiety and Type 1 diabetes.

“We all talk about that when you graduate from high school, they say you fall off a cliff because all the services and everything that you’ve been getting up until that point, you have to try to find a new way to get the services,” Bazik told me in a phone interview last week.

The program did secure Kibler with driving lessons in or around March 2019 because transportation is linked to employment.

But a subsequent termination of services, and the ensuing struggle to find new avenues of support, was a traumatic experience.

Bazik recounted her initial positive interactions with a counselor who showed promise in assisting her son’s employment prospects. However, after a change in counselors, communication breakdowns occurred, leaving Bazik and Kibler puzzled and deeply distraught over eligibility and available support. The changing requirements and lack of clarity further exacerbated the challenges they faced, Bazik said.

Around Dec. 1 of last year, Bazik and Kibler were stung by a very negative, jarring meeting where there was a dispute over eligibility. The meeting was with a program counselor, and Kibler’s therapist was also present.

“And then (the counselor) started to say, ‘Well, we’re going to close the case,’” Bazik recalled.

“(Hans) was pretty upset; the counselor said ‘case closed’ with him on the Zoom call,” she remarked separately. “He was so upset.”

The counselor insisted the family didn’t possess the right documentation.

“At that point, my son was at part-time status for college,” Bazik explained. “And I said, ‘Now I believe he qualifies for the support they give if they give support for the college.’ And he started coming at me with a list of requirements, ‘You have to prove this, you have to prove that.’ And I said, ‘Well, I was never asked to do any of that before.’ And then I said, ‘Okay, we’ll get these requirements.’ We have to have documentation from the college. We have to fill out the financial aid forms. There was a whole list of things that we had to do in order to get the assistance even though we had been approved in the past. And that was never explained to us.”

Bazik went about trying to obtain the requested documentation.

“But I could never satisfy the guy,” she recalled. “I went to the university. I asked for this letter from the registrar’s office. I told them what they wanted. They gave me it. I had all these documents. I mailed it to him, and they sent me a letter going, ‘No, this isn’t right. This isn’t right.”

When the counselor said “case closed” in the meeting, a startled Bazik tried to push back.

“And I said, ‘Wait a minute, you can’t say you’re closing the case,’” Bazik recalled. “I said, ‘My son has rights. He’s allowed to have these services.’ And I just felt like they wanted to just close the case. They just wanted to get rid of it. I mean, that’s how I felt. Whether or not they wanted to do that, I don’t know, but that’s how I felt at the time.”

Bazik still doesn’t even know whether her son’s case is closed or not; that’s just how dreadful and unclear communication has been with the program.

‘I Want This to Work’

One of the primary issues Bazik highlighted is the lack of a scaffolded support system.

She said ACCES-VR expects disabled young adults to advocate for themselves, but without the necessary guidance and resources, the expectation is too heavy.

A structured support system is needed to successfully navigate the complexities of job seeking.

“I really want this organization to work,” Bazik said. “I mean, I’m not a negative person. I want this to work. I want kids to be able to get jobs. I want this to work for people. I want kids who are going to college to get support. It’s important…I think there’s a lot of beliefs about people with disabilities. We want our kids working, living independently, but we need these services to help us.”

It’s also worth emphasizing how problems with the program in this region might be different to the way the program works elsewhere in the state. A friend of Bazik’s, who declined to go on the record, said the program runs far better in one upstate region. (There are 15 district locations across the state, including the White Plains office, plus 10 satellite offices.)

“One of the things that she said is when they went upstate, her son was looking at a college upstate, and this program there works effectively, but for some reason, it’s just not effective here,” Bazik recounted.

I even gained an extra kernel of anecdotal evidence to support what I was finding through interviews about experiences deteriorating when it came time for execution: my wife, a local public school teacher, came home last week to tell me about a colleague with a son in ACCES-VR; the co-worker was initially enthused after a positive initial meeting with a counselor. Then stagnation and communication failures took hold.

Hall of Fame Perspective

Yorktown’s Mel Tanzman, the retired executive director of Westchester Disabled on the Move, an independent living advocacy center based in Yonkers, enjoys more than three decades of experience in the field, and has two children who went through ACCES-VR.

“When I last heard, which was about a year (or) two ago, they had caseloads between two and 300 people,” said Tanzman, who was inducted into the New York State Disability Rights Hall of Fame in 2021. “So part of the issue has been with them that they don’t have enough case workers and they really don’t give enough kind of personal attention to everything.”

He emphasized that the program lacks personalized attention and often focuses on getting people into entry-level positions without considering long-term career paths.

Tanzman shared an example of a person with a paralegal degree who was placed in a job folding clothes at Walmart though the ACCES-VR program, despite being overqualified.

Based on my interviews, Tanzman’s anecdote appears to be representative of a common occurrence where some people are placed in dead-end positions and their cases are for all practical purposes closed, without further support or consideration for their goals.

“They don’t look at career path,” Tanzman told me in a phone interview last week. “All they care about is getting people into starting-level positions, and then the case is pretty much closed.”

He said ACCES-VR’s success is primarily measured by the number of people successfully placed in employment, without much attention to individual goals or outcomes, a point Meyers-Ruff disputes.

The program’s funding is tied to these statistics, Tanzman said, which contributes to a systemic and problematic checkbox mentality culture rather than focusing on comprehensive support.

Local program participants also better be prepared to be proactive, to have any chance of success.

“The amount of intervention that ACCES-VR will do really kind of depends on the initiative that the client may take,” Tanzman explained.

In the case of his son, he was provided with financial support for college but the program neglected to provide adequate assistance in navigating disabled student services. As a result, his son struggled and eventually had to leave school. A similar situation occurred with his daughter, who was placed in a retail position but lacked proper guidance and support from her job coach for the position to stick.

While the program displays effectiveness for some – Tanzman cited an example he knew of where lift equipment was purchased for a quadriplegic employee – the process is often painfully long due to the caseloads.

Never Say Never?

Lucille Rossi, a member of the Town of New Castle’s Every Person is Connected (EPIC) Committee, said she was only speaking for herself as an involved local resident, but noted how one success story I told her about through the local office of ACCES-VR was the first positive one she’d heard about in “10 years of paying attention.”

I actually later learned the success story I told Rossi about wasn’t a success story at all. The parent of a local developmentally disabled teen had to basically do all the advocacy herself, finding a job for her son. She subsequently alerted the counselor of the good news so the funding for the employment would run through the state, and not the employer’s bank account.

“I’ve never heard of anyone whose had a successful ACCES-VR experience,” said Rossi, who is also a member of the Westchester County Advisory Council on People with Disabilities but wasn’t speaking for the organization.

Rossi also mentioned an October 2021 state Assembly hearing on employment for people with disabilities that revealed persistently low rates despite promises from agencies for enhancement.

The state’s Office for People With Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD) must address the support gap for individuals who can work but need ongoing assistance, Rossi said. Tailored support, training and resources are needed for inclusivity.

“The biggest issue is that all the services out there are geared to people who can eventually work independently,” she pointed out. “But there are lots of people who can work, but will always need some support. There is really nothing in the system that supports them.”

Given ACCES-VR’s focus, Rossi’s now almost 23-year-old daughter, Mary Grace Sullivan, who has intellectual disabilities, was ineligible for the program, because she can’t work independently. (The state does offer other career service options).

Rossi also cited “customized employment” as a transformative strategy to achieve what’s called Competitive Integrated Employment (CIE). The approach identifies people’s passions, talents and business needs beyond traditional jobs.

As defined by the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, CIE is work where people with disabilities are compensated at or above minimum wage, receive comparable benefits, interact with individuals without disabilities and enjoy opportunities for advancement similar to non-disabled colleagues.

Ability Beyond

Agencies like Ability Beyond, the local nonprofit organization that works with families like the Diorios to deliver ACCES-VR benefits, also face systemic challenges of their own in providing services.

Tracy Conte, the agency’s vice president for development and community engagement, emphasized that finding employment partners is a time-intensive process that relies on extensive networking between counselors and businesses of all employment levels. Attracting and retaining employees has been a primary focus for several years, Conte said.

“We ourselves have enormous turnover,” Conte commented. “The rates of turnover are high, and attracting and retaining our employees is our number one business effort, has been for several years.”

The agency’s starting pay rates are generally set according to state funding, which tends to be low, Conte said. This, coupled with the fact that employees can often secure better-paying jobs elsewhere after receiving training and gaining experience, contributes to high turnover rates.

On an annual basis, the agency serves about 1,500 people through its career development services. The agency says it has 59 employment specialists across its New York and Connecticut locations but that figure includes seven open positions, including two here in our state. (There are more than 1,100 Ability employees overall across both states to deliver all of the organization’s services.)

“We are also limited in adding additional positions due to our budget restraints, and have gone so far as to seek private grant funding to cover salary for additional positions so we can serve more people in (New York) without success so far,” Conte explained.

Ability Beyond has been investing in creative retention initiatives, supported by fundraising, grants and PPP funds, to address the turnover issue, Conte added. This effort has helped reduce turnover rates to 24 percent this quarter from the industry average of nearly 50 percent annually during the pandemic, she also stated.

She underscored how issues with funding pose formidable challenges.

“Our industry was asking for 8.5 percent in the state budget and (only) four percent was approved,” said Conte, referring to a request to address cost-of-living increases for the industry, via the Office for People With Developmental Disabilities, noting how the 4 percent increase that was approved would help but how more remains needed “to make up for a decade of underfunding.”

“We just had our funding go through the legislature in both New York and Connecticut and it’s not enough,” she also said. “It’s never enough. We’re basically providing services at rates that were established in 2014.”

This means that policymakers eyeing the issue, hoping to tackle bigger picture reform, also need to advocate for fully funding outside agencies.

Conte said Ability Beyond maintains a strong relationship with ACCES-VR and receives referrals through the department. As for questions I asked about internal performance data, she said the agency tracks employment rates, placements and positive discharges, and boasts an extensive network of employment partners.

“We have hundreds of amazing success stories,” Conte said. (I asked last week whether Conte could connect me with a person or people directly, to hear local success stories firsthand. She tried but no one ever came through.)

Conte also pointed out how Ability Beyond’s job placement rate is significantly higher than the national average, as reported by the U.S. Department of Labor.

Through last month, for 2023, the labor force participation rate for disabled Americans ages 16 and over was a horrifying 24.3 percent. Conte said Ability’s rate is much higher, at 38.6 percent. (The 38.6 percent figure refers to the rolling employment rates of people in the agency’s career development services program who’ve gained jobs and remain employed.)

Labor force participation rate refers to the percentage of the population that is either employed or actively seeking employment. It includes individuals who are employed as well as those who are unemployed and actively looking for a job.

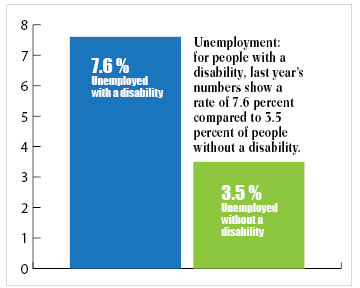

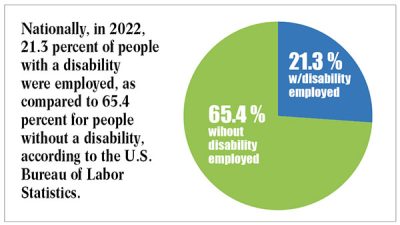

Nationally, in 2022, 21.3 percent of people with a disability were employed, as compared to 65.4 percent for people without a disability, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. As for unemployment, for people with a disability, last year’s numbers show a rate of 7.6 percent compared to 3.5 percent of people without a disability.

(Unemployment rates are different than labor participation stats, specifically referring to the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed and actively seeking employment.)

Despite all that, there is ample reason for encouragement. A source who did not want to be formally interviewed shared this nice nugget: Ability counselors, over the past 10 years, have noticed a marked improvement among employers when it comes to understanding the value disabled people can bring to their businesses as employees.

The Insider

This past weekend I was introduced to Bob Gumson, an Albany resident with a quarter-century of experience at SED before retiring in April 2017. He worked in the central administrative office of ACCES-VR, serving as a manager of independent living services.

Gumson acknowledged the overwhelming caseloads counselors face, unambiguously and candidly asserting that caseloads are way too large for effective service delivery to disabled people. He also drew from his own experiences, before his state education days, when he worked as a VR counselor in Massachusetts.

Even though Massachusetts is far smaller than New York, it maintained many more offices.

“Things could have changed all these years later when I left VR there, but they had maybe 29, 30 offices, all sprinkled in a state about a quarter of the population of New York,” he said. “So they were more community focused, and people could get to their offices and see counselors more easily there.”

When I informed Gumson about the increasing caseloads of local counselors, which can now reach or surpass 200 or even 300, going beyond the initially alarming range of 150 that he mentioned statewide from his experience, he expressed outrage.

“To really do it well, you shouldn’t have more than maybe 60 to 75 people,” Gumson explained.

He also shed light on another issue I hadn’t considered, and one no other source articulated. Even if there’s funding to add positions, and even if there’s the need to add positions, and even if there’s the desire to add positions, there’s still a bureaucratic brick wall standing in the way.

“Every time you need a new job or you replace an existing job, you have to go through an excruciating human resource process to get your requests approved, your headcounts of people that you have on your staff,” Gumson told me. “So let’s say the funding is there, okay? Let’s take them on their word and say there’s tons of funding. All right, so we want to reduce caseloads from 200 to 150. So we need 25 percent more staff to do that. You try getting 25 percent more headcount people into State Ed through the entire state bureaucracy system. It’s not just State Ed. It goes through the Department of Budget. It goes through the Office of the State Comptroller. They’re all afraid to expand capacity.”

Legislators need to be willing to support requests made by SED to increase staffing, he stressed, given the inclination of the Department of Budget to oppose almost any expansion of the government workforce.

Although there’s some state matching funds and other funding sources, most of the budget – about 80 percent – comes from the federal government, Gumson said.

The New York Office of Adult Career and Continuing Education Services was awarded more than $118 million by the federal government for vocational rehabilitation in Fiscal Year 2023, according to U.S. Department of Education records, meaning the overall budget is about $150 million, factoring in the state money.

When I asked Gumson about the best ways to achieve positive change, he also cited a bureaucratic aspect of the equation: Disability services, in his view, shouldn’t even reside within the walls of SED.

But how would his suggestion of moving these services into the Labor Department (or even creating a separate standalone agency) benefit the cause?

“It would be easier dealing with the human resource issues, getting staff replaced, maybe increasing staff, making its own decisions about how to market itself, tapping into if it’s part of the Labor Department, tapping into all the resources that Labor uses, market analysis and so forth,” he said. “Those are some of the possible benefits.”

Insider 2

Just this past Sunday morning, I met with a former state official to see if there were any holes in my reporting.

While the source couldn’t provide an exact figure, he said a “big number” of the 50,000 ACCES-VR program recipients are undeserving, with maybe somewhere in the 10 to 15 percent range – or maybe even higher – clogging caseloads, perhaps even a quarter or more.

I asked for an example.

“Somebody who had a shoulder injury and is going to have a corrective surgery, and it’s not going to be necessarily a chronic condition, or it’s not going to have any type of limitations from them being able to do the job that they were doing or the job that they’re looking for,” the official replied during a face-to-face interview on my porch. “That person should not be eligible for services.”

I was trying to understand why management would want big numbers. The source wasn’t sure, but I asked him to speculate, given his deep well of knowledge and insider insights.

“Personal ambition,” he replied, when pressed.

It’s just more impressive to boast of helping 50,000 New Yorkers, as opposed to, say, 35,000.

It’s the role of well-trained counselors to mitigate this problem, to professionally police the eligibility issue.

“If you start, like, losing the skill of a counselor to determine who’s eligible for services, which is that counselor’s most important job, right, is to determine who’s eligible for services, if you don’t focus on that anymore, and you just focus on just getting large amounts of numbers into that office and you don’t have the staffing to provide it, that’s a recipe for disaster,” the source said. “And that’s where you end up in situations where it could become a problem.”

There are also tons of job openings for counselors across the state, with a rough ballpark estimate of 90 vacancies, the state official said, highlighting an issue impacting departments across New York’s government.

ACCES-VR officials are keenly aware of the magnitude of the problem and anticipate increased challenges in hiring new counselors, according to the source. He said factors such as inadequate compensation and changes in the retirement system contribute to counselors finding it unappealing to work for VR.

State officials I spoke to also discussed the issue of assistants in the White Plains office.

To aid with the workload, there are vocational rehabilitation counselor assistants.

But due to inadequate staffing and high caseloads, assistants are often assigned other duties, leaving the counselors without the necessary support.

This causes a significant problem as counselors end up with almost double the recommended caseload as well as insufficient assistance.

“And what ends up happening is that the people that truly need the services, they don’t get the time or the quality of service that they’re entitled to,” the source said.

Call to Action

Meanwhile, one persistent theme that emerged in the process of reporting this story was the fact that sources believe reform likely requires more demand from the disabled community, to push lawmakers into action.

Interestingly, the press contacts of two local state legislators I spoke with by phone last week both said they have not been getting constituent complaints about these problems.

“We don’t, interestingly, get calls on a lot of issues that you would think that we would get calls about,” said Michelle Sterling, the chief of staff and director of communications for Assemblywoman Amy Paulin (D-Scarsdale). “And I think it’s a question of people just don’t know they can call their Assembly member and senator.”

Tom Staudter, spokesman for state Sen. Peter Harckham (D-South Salem), told me the same.

“We’ve heard nothing from anybody,” he said.

A press contact for Assemblywoman MaryJane Shimsky (D-Dobbs Ferry) echoed similar sentiments.

“As a state legislator charged with representing constituents in need of services as well as taxpayers funding the services, I am incredibly troubled to read the extensive details in this story, displaying a pattern of failures by ACCES-VR,” Mayer remarked in the opening of her June 13 statement.

Anyone inside government and politics will tell you just how much constituent service demand can impact public policy priorities.

And with the dire shortage of available counselors residing at the heart of the problem, or at least constituting a major component of where action is required, elected officials need to hear from voters and advocacy groups to be prompted into action and address a complex issue.

Policymakers should initiate collaboration between government agencies, educational institutions and nonprofit organizations and push for increased funding and resources.

Expanding counselor training programs and creating incentives for professionals to enter the field must be avenues of focus.

To effectively address the counselor shortage, it is also crucial to implement targeted recruitment campaigns and offer competitive compensation and benefits. In other words, it’s deeply complicated but entirely possible.

Final Notes

Holly Diorio suspects there might be a triage approach to the program, due to limited resources and staffing. For instance, because Maddie is far more ready for the adult world than many in need, her case was possibly deprioritized.

Maddie will be a freshman at Manhattanville in the fall, participating in the school’s Valiant Learning initiative, a support program designed to assist college-ready students with the management of academic challenges.

“Just because she’s college ready does not mean she’s going to be successful at college,” Holly said, when referring to any potential sense from ACCES-VR that Maddie isn’t in need of assistance. “She’s going to need help, she’s going to need resources and she’s going to need support. And that’s what ACCES-VR is supposed to provide, but they’re not doing their job.”

I asked how deflating the experience has been.

“She’s incredibly disappointed she probably will not have a job this year either,” Holly stated. “They keep saying they’re going to find something, they keep saying they’re going to help, but they haven’t done anything. It’s just empty promises, and it’s not fair to her.”

The pair of summers after junior and senior years of high school in particular are unique time periods for adolescents, offering two special windows for regular employment before the next phase of life.

I wondered if the opportunity has been squandered as a result of ACCES-VR’s fumbling.

“We’re in the throes of transitioning to college now,” Maddie’s father, Ken, told me in a phone call last week. “That’s kind of taking priority lately.”

The Diorios pour their hearts and souls into Maddie’s development. I’ve seen firsthand how much she’s blossomed under their loving advocacy. They seem to press every conceivable button to optimize Maddie’s future.

As a local educator herself, Holly is as savvy, persistent and effective of a parental advocate as you can imagine, while Ken’s unconditional love for Maddie oozes from his pores.

Their daughter’s growth has been remarkable to observe from afar over the past eight or so years, since I met the family.

Not all people with disabilities are that lucky. We need strong institutions in place to lift up the most vulnerable among us.

If there is one issue that could invite bipartisan cooperation and policy brainstorming, where the undeniable necessity of public support for those in need of services cannot be disputed, it is right here in this general space, helping the disabled.

While breathtaking progress has been achieved in recent decades, there is still much work to be done.

Disabled New Yorkers deserve much more than broken promises and bureaucratic snafus.

Inclusion isn’t just a buzzword. In this context, it’s about reform that enables the disabled. It’s about providing people with the capes they need to soar. And the tools they need to shatter glass ceilings we neglected to even consider possible in past generations.

Adam has worked in the local news industry for the past two decades in Westchester County and the broader Hudson Valley. Read more from Adam’s author bio here.

Staffing Woes

Staffing Woes