Making It

News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

At an innovative incubator for makers in Tarrytown, a new generation of craftspeople embraces the life-affirming magic of creating things by hand.

Good morning! Today is Wednesday, January 12, and you are reading today’s section of Examiner+, a digital newsmagazine serving Westchester, Putnam, and the surrounding Hudson Valley.

Need to subscribe — or upgrade your Examiner+ subscription?

Join the community as a full-fledged member with our special FREE TRIAL OFFER for the New Year: Enjoy 30 days of total access to Examiner+ for no charge. Offer expires at month’s end.

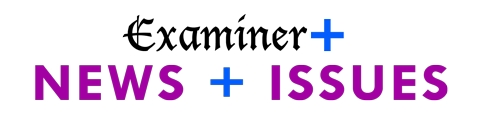

It was the Sunday after Small Business Saturday in late November, before Omicron’s onslaught, when a semi-normal holiday seemed possible. Most of the year, Makers Central, a former industrial garage on Central Avenue in Tarrytown, is a noisy place, with lots of banging, sawing, and drilling, the sound effects of the makers’ trade. This place is unique in Westchester, a sort of co-working space with large power tools, where tiny businesses can rent square feet to make their products. But for two holiday weekends a year, the big metal doors open to the public so the makers can, well, make some money by transforming the location into a pop-up artisanal market.

The feeling was festive and unstudied. Draped canvas and butchers paper loomed large in the decorating scheme. Masks and Covid-tracking information were required before entering; and the shoppers, many pushing strollers, followed a prescribed route up one side and down the other, sipping small-batch whiskey (hillrockdistillery.com) while admiring concrete vases and planters, ceramic dinnerware, and burnished knives of Damascus steel that look lifted from a Game of Thrones set.

Unlike most pop-up holiday markets, the big tools — lathes, anvils, table saws, kilns — are part of the scene here. At the carpentry business, a dad showed his sons the finer points of a large table saw, draped with a boho garland. Outside, a happy customer raced down Central Avenue, clutching an intricate cutting board made with that very same saw.

Take a moment to evaluate your own holiday gift haul. Chances are it includes something handmade, small-batch, out of the ordinary, created by a dedicated craftsperson in his or her kitchen or basement, and sold at one of the many “makers markets” that popped up this past holiday season. A hand-poured scented soy candle with a cotton wick and a clever name (jarworthy.com). A knit cap using hand-dyed wool from sheep that graze in organic pastures (twoknitwits.com). A necklace made with upcycled parts from vintage jewelry (Adzineny.com) or strung with seed pods from the Amazon rainforest (natural-sur.com). Once a term applied to high school robotics and 3-D printing, “maker” has come to define anyone who makes goods by hand, from scratch, or as close as possible, using methods and materials that won’t dent the environment. It’s a deeply personal and often solitary pursuit, the antithesis of disposable, distant, mass-produced.

“Making” has become a global movement, goosed along by an endless pandemic, fractured supply chains, and a strong shop-local ethos. Millennials especially appreciate sustainable, locally sourced products that won’t end up in the trash or recycling bin after a few uses.

“The makers’ movement is about bringing creativity, inspiration, and socially responsible economic growth to our communities,” says Amanda DiRobella, associate publisher of four Edible publications in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Hudson Valley, and Westchester. “We’re witnessing the strong re-emergence of, and reliance on, our local artisans and small businesses.”

Making It Happen

At the Makers Central Holiday Market, Connor McGinn stood near the front in his pottery studio, surveying the scene. Blue-eyed and ginger-stubbled, the Carmel native developed his culinary chops at Restaurant North in Armonk (“My title was ‘Mercenary’; I did everything”), and now sells his exquisitely minimal dishes to high-end restaurants.

McGinn gets his clay ingredients and glazes from out of state, but otherwise, his supply chain stretches from his potter’s wheel to his kiln to these racks and shelves. This comes in handy when he has to whip up fresh inventory. After receiving an unexpected order for plates from Goosefeather in Tarrytown, he was low on stock for the Holiday Market. He spent a week loading and unloading his kiln, and pulled out his last batch of bowls, plates and mugs just as shoppers were walking through the door, the pieces so fresh he had to warn them to be careful because they were still hot.

“My supply chain involves a lack of sleep.”

Like everyone at Makers Central, McGinn is in his 30s, whip-smart, and passionate about the maker’s life-affirming mission. Nine small businesses rent here, and there’s a culinary twist: Half of the makers have worked at Blue Hill at Stone Barns, the legendary farm-to-table restaurant in Pocantico Hills. Makers Central is a place for them to build a second act; to explore, experiment, and hopefully profit off their own creativity and talent, working as a community to support and uplift their efforts.

“We have so many people from the food world because it’s all about stories,” McGinn explains. “They’re intertwined in this desire to have some sort of meaning, whether it’s stuff you eat or stuff you use.”

Yes, his dinnerware costs more than your average plates, but there’s value in the process.

“You could purchase a bowl with the exact same function from Target, but I’m not selling the ability to hold cereal in a vessel,” he argues. “I’m selling a story, of people and their products… If somebody purchases that product from the person who made it in the space with all the tools used to make it, it’s the richest environment for telling that story. Buying stuff off Amazon, you have no idea who made it and how many different hands touched it before you got it.”

Making It Click

Stetson Hundgen, co-founder of Makers Central, agrees. “Makers understand how it feels to make something with your hands that you know will last lifetimes, generations perhaps, and put it out into the world. It’s a piece of you.”

A native of Northern Westchester, Hundgen grew up around small business: His mother owns a flower shop in Chappaqua and counts the Clintons among her longtime customers. An executive assistant, property manager, and tireless idea-maker, he threw together the charmingly unstructured wreath hanging over the Holiday Market; his latest venture is an organic bird food (shop.flyingcolors.co). Several years ago, Hundgen stopped by the Twisted Oak in Tarrytown for a drink and met McGinn, who was tending bar while making pottery as a side hustle. They became friends. McGinn had outgrown his studio space in Port Chester, and Hundgen knew of an available commercial building in Tarrytown. It was far bigger than McGinn needed, so they hit on the idea of subletting parts of it to other maker-entrepreneurs.

“Having people around that are like-minded and have the same kind of ideals and struggles helps to incubate creativity,” says Hundgen. “We’re tied together through a shared passion. We lean on each other.”

And since the makers produce items for the hospitality business, Makers Central has become a one-stop-shopping experience for restaurants and hotels. When potential clients come to see McGinn’s dinnerware, “they’re naturally drawn to the other members.”

Making It Art

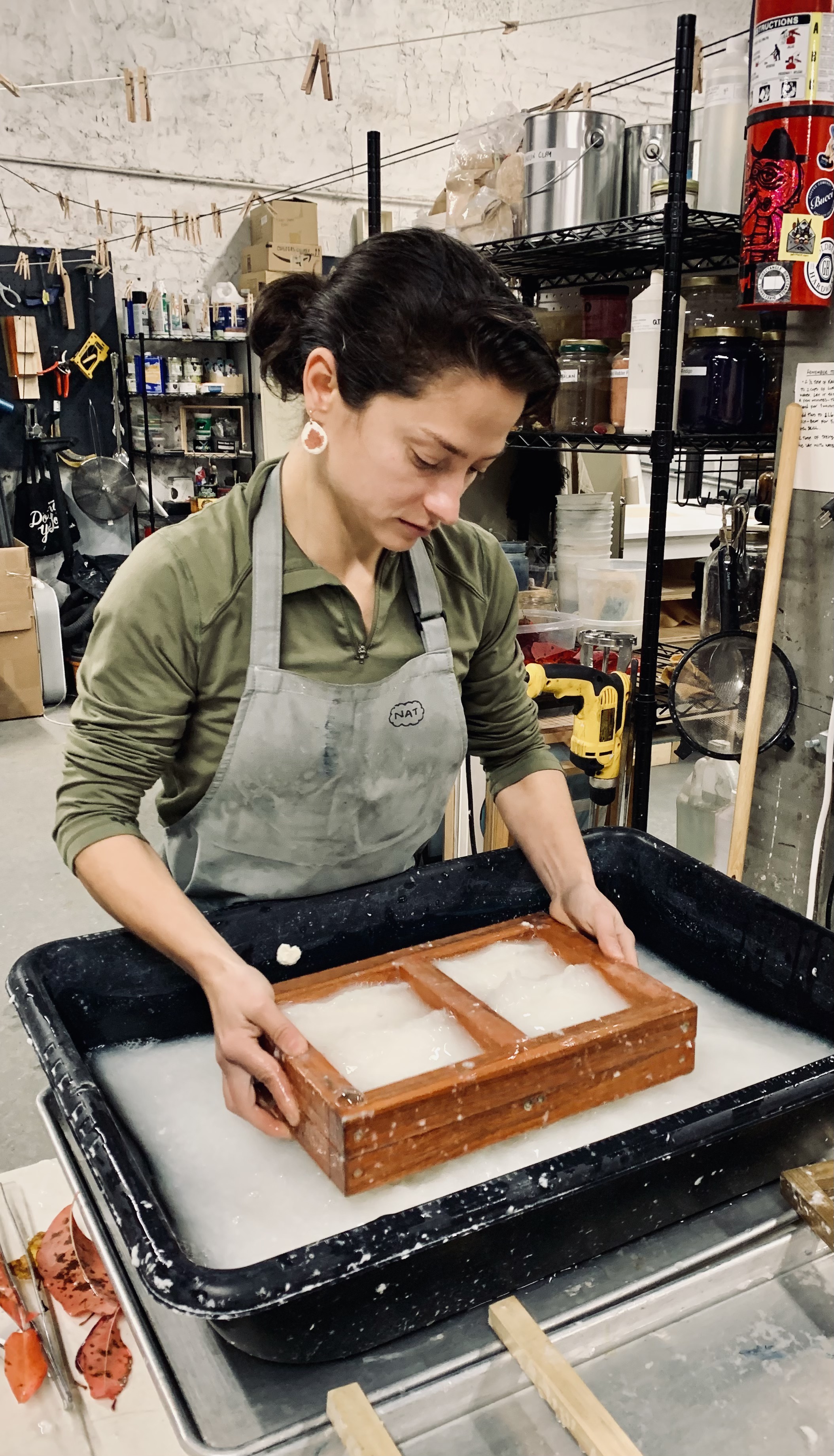

One of them is his partner in business and life, Natalia Woodward, founder of Bat Flower Press. Woodward’s designs are meticulous and spare. The SUNY Purchase grad draws inspiration from nature and the handicrafts industry in her native Colombia. “Handmade is a way of life where I’m from; it was ingrained in me growing up.”

Of all the machines at Makers Central, arguably the coolest is “Gretta,” Woodward’s massive cast-iron letterpress, a relic of America’s industrial past built in 1903. She located the press upstate, hauled it down to Makers Central, and named it for Hundgen’s childhood dog. Woodward draws her designs by hand, scans them into a computer, has them made into polymer plates, and then reproduces the images on Gretta using water-based inks. Originally operated with a foot treadle, the press has been electrified and can print 200 pieces an hour, about the same as your average copier.

“This traditional vintage style of printing is coming back more and more these days,” says Woodward. “Digital printing doesn’t have the feel that letterpress does.”

She even makes her own paper, using waste fibers and foraged plants. These include Japanese knotweed, an invasive species abundant in Westchester, and stubble from the rye and wheat harvests at Stone Barns. Her cotton paper comes from old matte boards from MOMA, where she works as an art preparator in the Drawings and Prints Department. She boils the fibers down on a propane stove, blends them to a pulpy mash that’s shaped and flattened into sheets, which she dries on clotheslines. From this highly textured paper, she creates custom wedding invitations and stationery on Gretta for hotels and restaurants, including Blue Hill, where she once worked as a captain before pivoting to art full-time.

“I had some money saved, and I said, ‘I have to do something different with my life now.’” Her new title? “I’m a waste collector!”

Making It Last

Sustainability is key to the makers’ creed. At C-Los Carpentry (c-loscarpentry.com), Carlos Chimborazo and Elena Krougliak use only fallen wood for their free-form bowls, which they air-cure for a year before selling.

“We make everything from scratch, crafting something new every time,” says Krougliak, who also designs and builds custom furniture and cabinets. “To us, it means we support people in our community rather than buying something that’s been shipped from overseas.”

At Pivot Concrete, Deion Jones and David Puchalski produce planters, trays, and assorted vessels made from their bespoke concrete blend. For their candles, they acquired a bunch of beef tallow from the Butcher Girls in Dobbs Ferry, which would otherwise go to waste. They boiled the fat down on the stove in the Makers Central kitchen. “It was a very savory few hours,” says Jones wryly.

Sylvia Lukach of Cape Lily (capelily.com), a floral artist across the aisle from Woodward, shares her botanical leftovers with the artist: “I’ll ask, ‘Hey, can you turn this into dye? Do you want to do anything with these petals?’ We’re all using each other’s by-products.”

Making It Grow

This collaborative approach is what drew Lukach to Makers Central. Originally from South Africa, she shares her area with event planner Michelle Edgemont Design (michelleedgemont.com). Her work is art, and she paints with flowers. While Holland and Latin America are leading flower producers, she works hard to buy her seasonal, chemical-free blooms from Hudson Valley farms like Stars of the Meadow in Accord (starsofthemeadow.com).

Lukach makes remarkable floral art pieces for Makers Central’s Sunday Supper Club. That’s when McGinn and Hundgen turn the space into an industrial-chic dining hall and invite the public to enjoy a tasting menu prepared by a local chef (and served with the makers’ pieces, of course). This year, the plan is for Sunday Suppers every month starting in February. “It’s a blank canvas for me to do something wild,” says Lukach. “Last year we did an art piece hanging above the table, showcasing marigolds.”

Help is all around her. If Lukach needs an ornamental arch welded, she goes to the bladesmith, Matt Yazel. If she needs vases, she turns to the guys at Pivot.

“We struggle to find good containers in our industry, especially during Covid; there’s been such a backlog in shipping. I wait months for them to be delivered, so it’s useful to have them made right next to me.”

Making It Rise

Chase Harnett, founder of The Hudson Oven (thehudsonoven.com), doesn’t rent space at Makers Central, but he’s “part of the fam there.” Only 26 and hailing from Piermont, the Stone Barns alum is a truly modern maker, combining an analog product (sourdough bread) with digital marketing savvy.

Most Sunday mornings, in a garage in Ossining, Harnett bakes dozens of loaves in a wood-fired oven parked in the driveway. He places them into a large cabinet, drives it to an undisclosed location in Westchester County, and leaves it there, guerilla-style. (This sort of makes him the Banksy of bread.) He emails the 3,200 people on his subscriber list, giving them a head start, before posting the location on Instagram. His followers track down the cabinet and grab a loaf, leaving what they think it’s worth in a metal box.

The real dough comes from “bread memberships.” He stores loaves of his sourdough in large antique metal filing cabinets located in Nyack at the Gene Reed Gallery, Dobbs Ferry at Hudco, Ossining at Sing Sing Kill Brewery, and here at Makers Central in Tarrytown.

“When I was looking for locations to have a bread locker, this was the first place I went to,” he says. “They’re like-minded, and I thought they could dig it… It’s an interesting type of person that chases around a cabinet full of bread on a Sunday morning. That’s the same kind of crowd that would enjoy the things made at Makers Central.”

Harnett’s latest product is the Bread Brick, a blend of his sourdough starter and freshly milled flour from upstate. Just add water and bake. Next up: a Pizza Brick.

He makes real bricks, too. Last summer, he and a friend were commissioned to create a Colonial-era bread oven at Philipsburg Manor in Sleepy Hollow. Harnett went total old-school, from digging up clay and sand along the Hudson River to shaping the bricks in period molds and drying them in the sun. Using the bricks, he built a beehive-shaped oven that will be another teaching tool at the site.

Watch the video:

Like Woodward with Gretta, Harnett finds inspiration in the past.

“Somewhere during the Industrial Revolution, it became normalized to engineer food, and not always for the better,” he explains. “These old ways of doing things are a way for me to start from the origin and try to define a new modern view on food because I feel there is much to fix with the current one.”

Making It Matter

Matt Yazel, bladesmith (Yazelknives.com), makes knives — not your ordinary home-store cutlery, but burnished blades of Damascus steel and sculpted handles. “The first few times you hit a piece of hot metal, it changes you,” says Yazel of his early experiences with blacksmithing in Massachusetts, where he worked the red-hot Boston restaurant scene for two decades. “I was always trying to find myself. My wife said, ‘Find a passion.’ Until this, nothing captured my interest.”

At 39, Yazel is the oldest maker here. He has created a cutlery kingdom in the back corner, with all the tools he needs to mash, shape and hammer raw steel into blades. There’s a forging press and a power hammer, a forge and a blacksmithing anvil — “the island of my kitchen” — and a separate grinding area. His craft requires fire, force, improvisation, and artistry. Making things, says Yazel, “is a passion-driven business. We have all decided to live our lives differently than mainstream society. I think that’s really brave.”

Playing with fire comes naturally to Yazel. “A lot of little boys were pyromaniacs. When I was seven, I got in trouble for lighting my shoelaces on fire in my bedroom.” His goal is to buy a place and build his own workshop “and make some real fireballs!”

While his blades may be wicked sharp, Yazel himself is a softie when describing his life-changing journey to full-time bladesmith — he’s making, not just knives, but a life where he calls the shots, grounded in a craft that is millennia old.

“I feel connected to humanity in a way I hadn’t before. Now that I’m working by myself, I’m starting to feel like a real person. It’s just me, figuring things out… I’m going to make zero money and ensure my time is spent fortifying my soul instead of just surviving. There are a lot of people in the same boat, trying to make sense of their lives.”

Freelance writer and Ossining resident Dana White was thrilled to combine her passions for shopping and wordsmithing in one article. She is not crafty in the least but enjoys making toast.

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.