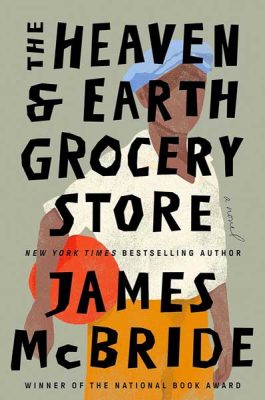

‘Heaven’ Help Us, McBride’s New Novel Soars

Review An assessment or critique of a service, product, or creative endeavor such as art, literature or a performance.

By Michael Malone

“The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store” is about a neighborhood, a not-all-that-desirable district in Pennsylvania where Jewish immigrants and African Americans lived side by side, with a few Italians and other European immigrants mixed in.

“The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store” is about a neighborhood, a not-all-that-desirable district in Pennsylvania where Jewish immigrants and African Americans lived side by side, with a few Italians and other European immigrants mixed in.

The neighborhood is known as Chicken Hill, near Pottstown, and the book is set in the ‘20s.

Moshe runs a dance hall in Chicken Hill, where Jews and Blacks alike see live music and unwind. His wife, Chona, sickly but with a spine of steel, runs the Heaven & Earth Grocery store, where the kindly proprietor sells victuals or, more frequently, gives them out to customers who promise to pay her back. Moshe and Chona live upstairs.

There is a 12-year-old boy in Chicken Hill who is known as Dodo. A stove exploded in his home, ruining both his eyesight and his hearing. The eyes came back, but the ears did not.

And so everyone calls him Dodo. He is an orphan. The state sends agents to find Dodo, as it wishes to put the boy in an institution.

Residents of Chicken Hill, including Chona, hide Dodo from the government reps.

The Blacks and Jews have some things in common other than their run-down nabe. They are struggling to find work and money and food. They are in the margins of Christian white America. They mostly stick together.

Indeed, the white population is not all that welcoming of the outsiders. There is a KKK offshoot known as the White Knights, which counts a prominent local doctor among its robe-wearing faithful. He is known as Doc.

James McBride wrote “The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store.” He writes of the White Knights from Doc’s perspective: “They wanted to preserve America. This country was woods before the white man came. It needed to be saved. The town, the children, the women, they need to be rescued from those who wanted to pollute the pure white race with ignorance and dirt, fouling things up by mixing the pure WASP heritage with the Greeks, the Italians, the Jews who had murdered their precious Jesus Christ, and the n*****s who dreamed of raping white women and whose lustful black women were a danger to every decent, God-fearing white man.”

McBride, an African American, wrote the n-word out.

Doc has long lusted after Chona. When she suffers a seizure in the shop, Doc tends to her. Thinking no one can see them, he ends up molesting the passed-out woman. But Dodo, who is hiding, sees it all. Ever loyal to Chona, he goes ballistic.

Dodo ends up in an institution. It is a bleak insane asylum. He is stuck in a room with a severely disabled boy in a crib who does not speak.

“The boy looked as if he had tied himself up in knots and was hiding from himself,” McBride writes of the youth Dodo refers to as Monkey Pants.

The two boys initially struggle to communicate. “So they went at it again, driven only by the aching loneliness of their existence, two boys with intelligent minds trapped in bodies that would not cooperate, caged in cribs like toddlers, living in an insane asylum, the insanity of it seeming to live on itself and charge them, for despite the horribleness of their situation, they were cheered by the tiniest of things, the crinkle of an eyelid, an errant cough, an occasional satisfied grunt or burst of laughter as one or the other bumbled about in confused impatience at the other, trying to figure out how to communicate the origins of Monkey Pants’s precious marble,” McBride writes.

That is quite a sentence.

Whether the good folks of Chicken Hill can bust Dodo out of the asylum, known as Pennhurst, drives the back half of the novel.

While I was reading it, the Malones watched the 2019 horror film “Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark,” it being Halloween week and all. Oddly enough, that movie, set in Pennsylvania, also had an insane asylum known as Pennhurst.

Apparently, there was a real Pennhurst, which was initially known as the Eastern Pennsylvania Institution for the Feeble Minded and Epileptic.

McBride’s novels include “The Good Lord Bird” and “Deacon King Kong.” While the new novel is set around 1925, McBride has some things to say about American society a century later, including those who fear that immigrants streaming over our borders will pollute America’s pristine waters.

“The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store” has been very well-received. Nearly 20,000 people have rated the book on GoodReads, and it is averaging a glittering 4.31 out of 5. The New York Times called the book “a murder mystery locked inside a Great American Novel,” and “a charming, smart, heart-blistering and heart-healing novel.”

The Washington Post said, “With his eccentric, larger-than-life characters and outrageous scenes of spliced tragedy and comedy, ‘Dickensian’ is not too grand a description for his novels, but the term is ultimately too condescending and too Anglican. The melodrama that McBride spins is wholly his own, steeped in our country’s complex racial tensions and alliances.”

I loved it as well. McBride’s prose is alternately a punch in the gut and a pas de deux. Chona, who walks with a limp, is prone to seizures, and offers kindness to most everyone who enters her grocery story. She’s an unforgettable character. Dodo is too. His scenes with Monkey Pants in the grim asylum will stay with the reader long after they close the book.

McBride was inspired to write the novel by the director of a camp for handicapped children in Pennsylvania, where the author worked for four summers during college. McBride’s gift to his old camp director, Sy Friend, is one we all can unwrap and enjoy.

Freelance journalist Michael Malone lives in Hawthorne with his wife and two children.

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.