From Westchester to Stockbridge: My Rockwellian Weekend Journey

News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

Mamaroneck’s famous son changed American identity.

Good morning — and Merry Christmas Eve! Today is Friday, December 24, and you are reading today’s section of Examiner+, a digital newsmagazine serving Westchester, Putnam, and the surrounding Hudson Valley.

A message from our Editor:

This morning I’m pleased to present another essay from our Publisher, Adam Stone, who reflects on a recent trip to my go-to happy place, The Berkshires in western Massachusetts — and specifically, the Norman Rockwell Museum.

People who dismiss the idyllic scenes of home and hearth that Rockwell painted as mere fantasy need only drive two hours up the Taconic to spend time in the Berkshires and see that lifestyle is very real, alive, and well — especially now at Christmastime, when a stroll down the main street of Stockbridge feels like you’ve stepped into one of Rockwell’s paintings. For Rockwell didn’t paint imaginary places or figures — he used friends, neighbors, townspeople, even his own sons, as subjects for his works. In fact the Museum holds periodic meet-and-greets with his surving painting subjects, who share fond memories about their experiences modeling for Rockwell.

While not as widely known, as Adam notes, it is the second act of Rockwell’s career, where his works begin to convey his deepening social conscience, that helps to cement his place in the pantheon of iconic American artists.

Enjoy Adam’s story — better, still, follow his advice and take a trip to enjoy Rockwell’s works and the area from which he drew much of his inspiration.

Robert Schork, Digital Editorial Director

Need to subscribe — or upgrade your Examiner+ subscription to enjoy full access to all of our premium digital content? Details here.

Join now and take advantage of our special holiday rate of just $39 for a whole year:

Today’s Examiner+ is sponsored by Greca Mediterranean Kitchen+ Bar in White Plains.

For every million Joe Schmo creators, for every dreamer whose art vanishes unheralded in the ceaseless passing of time, there’s one whose work captures the world’s attention and maintains that grip across a broad span of history. Their contributions endure in our minds, in our collective consciousness, burning a flame in our imaginations while art of equal or superior (and lesser) technical quality or artistic ambition evaporates into ash. It isn’t preordained, the select few who win the rare place. It is the byproduct of not just hard work and talent but also coincidence and serendipity. Timing and chance. Artists who possess greater ability descend into anonymity. But there’s that rarity, the one who bends history with the strum of a guitar, or the turn of a phrase, or the stroke of a paintbrush. They might have elite skill but it’s their penchant and passion for storytelling, in the right historic moment, with the right megaphone, that sets them apart and elevates their legend, mixed with elements of luck and happenstance — right person, right place, right time. In 20th century American writing, think Hemingway. In music, think early Dylan.

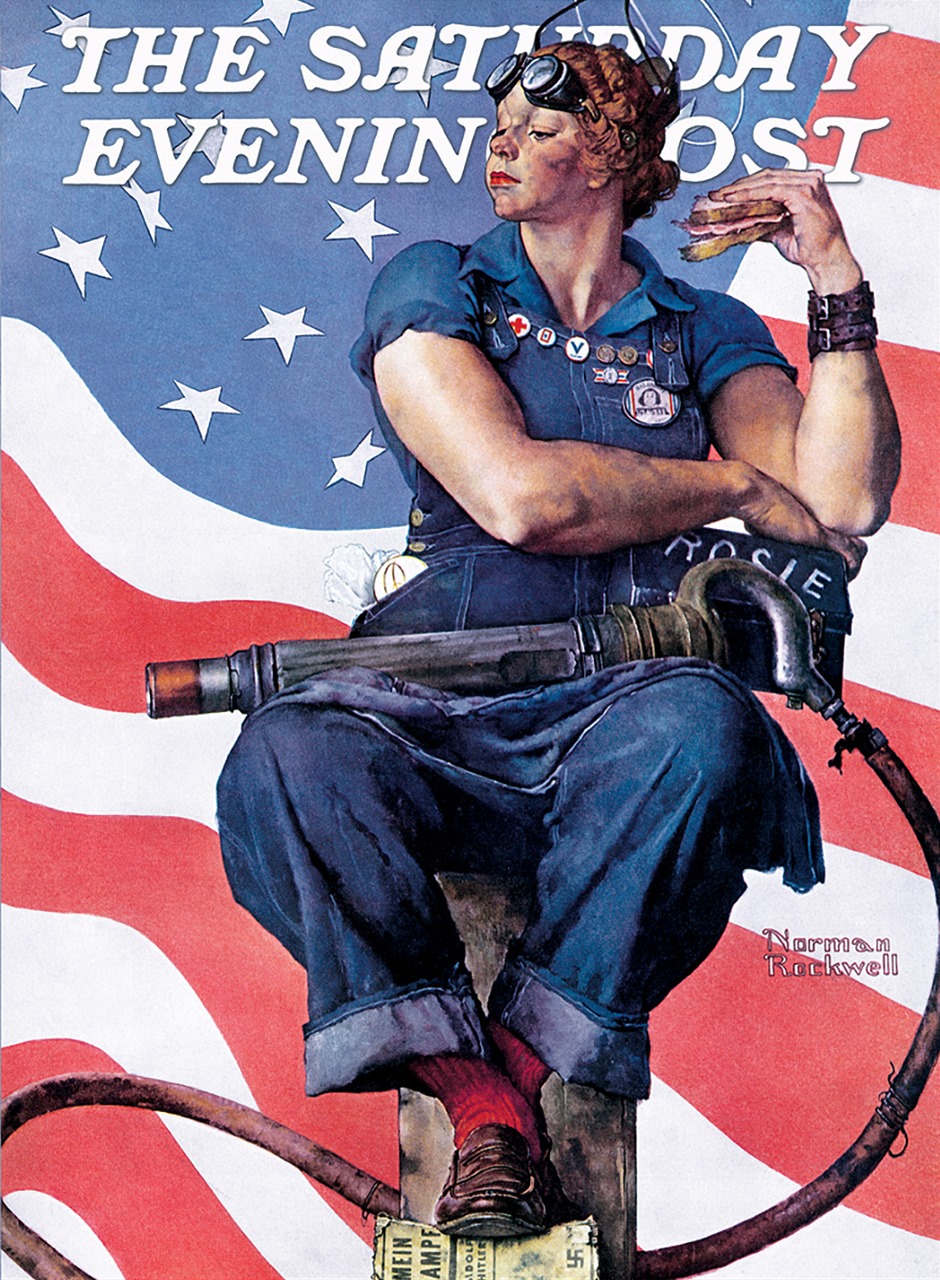

In modern American life, no painter/illustrator fits that description better than Norman Rockwell, a Mamaroneck High School dropout who delivered America, especially suburban, middle-class America, a new national identity. And examining Rockwell’s influence over our identity has never been more relevant than it is today.

Just think, heading into last year’s presidential election, a whopping 80 percent of voters on both the Republican and Democratic sides proclaimed that contrasts with the opposing party are about core American values. But what are those values? And who helped shape them? No figure of the 20th century did more than Rockwell to create a visual vocabulary for us around those values, creating both American myths and real aspirations.

Roadtrip

All sober ruminating aside, and with just a fun getaway in mind, my wife Alyson and I recently visited the Berkshires for a weekend and included a pitstop at the Norman Rockwell Museum in his adopted adult life hometown of Stockbridge, Massachusetts. But I came away from the experience inspired by Rockwell’s legacy, with a wider understanding of the impact he had on how we look at ourselves as Americans. Moreover, even a cursory examination reveals Rockwell’s work to have created something of a subtextual starting point for what both liberals and conservatives are really debating in our cacophonous culture wars.

In Rockwell’s Four Freedoms, inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous speech, liberals see America, in its grandest ambitions, as animated by civic engagement and communal opportunity while conservatives see familial strength and the benefits of religious bonds. Narrative is in the eye of the beholder.

Although his overall body of work is more complicated than the shorthand his name evokes, it’s easy to understand why Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan would appeal to voters who imagine early Rockwell’s rosy depiction of the country in their mind’s eye as the picture of our idyllic, less multi-cultural, more prosperous past. And it’s just as easy to understand why that appeal conjures a racial dog-whistle for condemners of the slogan, myself included.

But as Rockwell’s career progressed, he grew more socially conscious and less inclined to just shill for advertising interests. In The Problem We All Live With, his illustration in Look magazine of Ruby Bridges, the six-year-old African-American girl being escorted to her first day at an all-white New Orleans school by U.S. Marshals, Rockwell delivered the world a jolt of vivid reality, reminding the country how our shared ideals were not being shared at all. The image of splattered tomatoes and the N-word scrawled on the wall behind Bridges are tough to look at but 1964 Rockwell made us look. Few iconic Civil Rights images achieved more in changing hearts and minds. In fact, Rockwell left The Saturday Evening Post for Look the prior year because of resistance to addressing important political themes at the Post.

Suburban Fantasies

It’s also easy to forget that in Rockwell’s early life and career, at the turn of the century, the figures that Americans looked back on weren’t, well, Rockwellian. The narrative tapestry of the quintessential American life was still being stitched. The puritanical worldview remained a dominant force in our national identity. Think more the stern farmer and farmer’s daughter in American Gothic, less Don Draper.

But here today in Westchester County, a quintessential U.S. suburb, with all its myths and fables, residents strive for a certain Rockwellian ideal, an image of middle-class American life portrayed today in carefully curated social media posts of smiling children, glorious food, and wonderful vacations. Rockwell’s The Saturday Evening Post might have been replaced by Zuckerberg’s Facebook and Instagram but the artist’s rendering of America, both in ways correctly and incorrectly interpreted, continues to advise our view of living your best life.

While the traditional Rockwell reference might cause us to imagine a stereotypical 1950s middle-class suburban family enjoying a picturesque, bountiful Thanksgiving dinner, the stories of many of our families start with ill-fed people hungry for a better life, before achieving it.

I began to think about my family and my wife’s family, and how we fit into the understanding of American life pre- and post-Rockwell. I thought about my father, and his immigrant journey from Budapest, Hungary to Haifa, Israel to Genoa, Italy, to Long Island, New York, and how growing up in communist Hungary he dreamed of a “shining city on the hill,” a rhetorical image borrowed and brilliantly popularized by President Ronald Reagan but given an aesthetic by Rockwell generations earlier. I also thought about Alyson’s father’s family.

Today’s supporting sponsors are the Town of Yorktown…

…and the Peekskill Business Improvement District.

Are you serious?

My father-in-law Ken Foley’s maternal grandmother, Bridget Agnes Garvey, was just 14 in 1912 when she shipped off to Boston Harbor by herself from her hometown of Claremorris in County Mayo, Ireland, to begin her American story as a housekeeper. By the time she was in her early 30s, and in the shadow of the Great Depression, she savvily purchased a home at 722 Prospect Avenue in Mamaroneck from her struggling landlord, giving the new American family an asset that would enhance its fortunes and remain in the tribe from 1929 until Ken’s mother died in 2012. Incredibly, as I learned in Deborah Soloman’s definitive biography (American Mirror) while contemplating all this, the address of the rented home where Rockwell spent his early 20th-century youth: 415 Prospect Avenue in Mamaroneck, a stone’s throw from my father-in-law’s boyhood home on the same street, a historical family tidbit we never knew until this writing.

The contradictions and complications in interpreting American life through Rockwell’s lens are showcased in Rockwell’s own life, starting from that period in Mamaroneck where he felt inadequate as a skinny, awkward kid, jealous of his athletic, handsome older brother Jarvis. Eventually thrice married with a strained relationship with his three sons, riddled with anxieties and self-doubt, Rockwell struggled with personal demons antithetical to the muscular, masculine American portrait he painted in his earlier work.

A Two-Hour Tour

But amidst Rockwell’s creations, even if digested differently in various quarters, and even if a departure from his own experience, Americans were at least living in a time when our national story could be absorbed en masse. In today’s fractured news environment, where we turn to content to confirm our biases, it’s easy to forget we once lived in a country, for better and for worse, where mass media ruled the kingdom. The Saturday Evening Post alone boasted of reaching two million mostly middle-class homes per week. Given the fact that he created the cover art for 323 front pages in The Saturday Evening Post over 47 years, Rockwell delivered a mind-boggling bundle of bourgeois cultural sway in that half-century.

So if you’re looking to gain a richer understanding of Rockwell’s work, or if you’re just seeking an excuse for a weekend day trip to escape, be sure to add the easy drive to Stockbridge to your to-do list, including a visit to the museum. It took us just two hours from Mount Kisco.

Whether you’re liberal or conservative or moderate or politically agnostic or anything in between, there’s so much to learn from Rockwell’s career and his influence on the way we all process what it means to live an American life.

Rockwell is truly that one-in-a-million artist whose voice continues to speak to us today, whether we hear it or not.

To learn more about the Norman Rockwell Museum, visit www.nrm.org.

Adam Stone is the publisher of Examiner Media. When not running local news outlets or chauffeuring his children, Stone can be found on the tennis courts at Mt. Kisco’s Leonard Park, on his iPad playing chess, or on the floor cleaning after his two dogs.

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.