Dignity in Life, and in Death

News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

Mid-Hudson advocates strive to legalize medical aid in dying.

Good morning! Today is Tuesday, November 9, and you are reading today’s section of Examiner+, a digital newsmagazine serving Westchester, Putnam, and the surrounding Hudson Valley.

Need to subscribe — or upgrade your Examiner+ subscription to enjoy full access to all of our premium digital content? Details here.

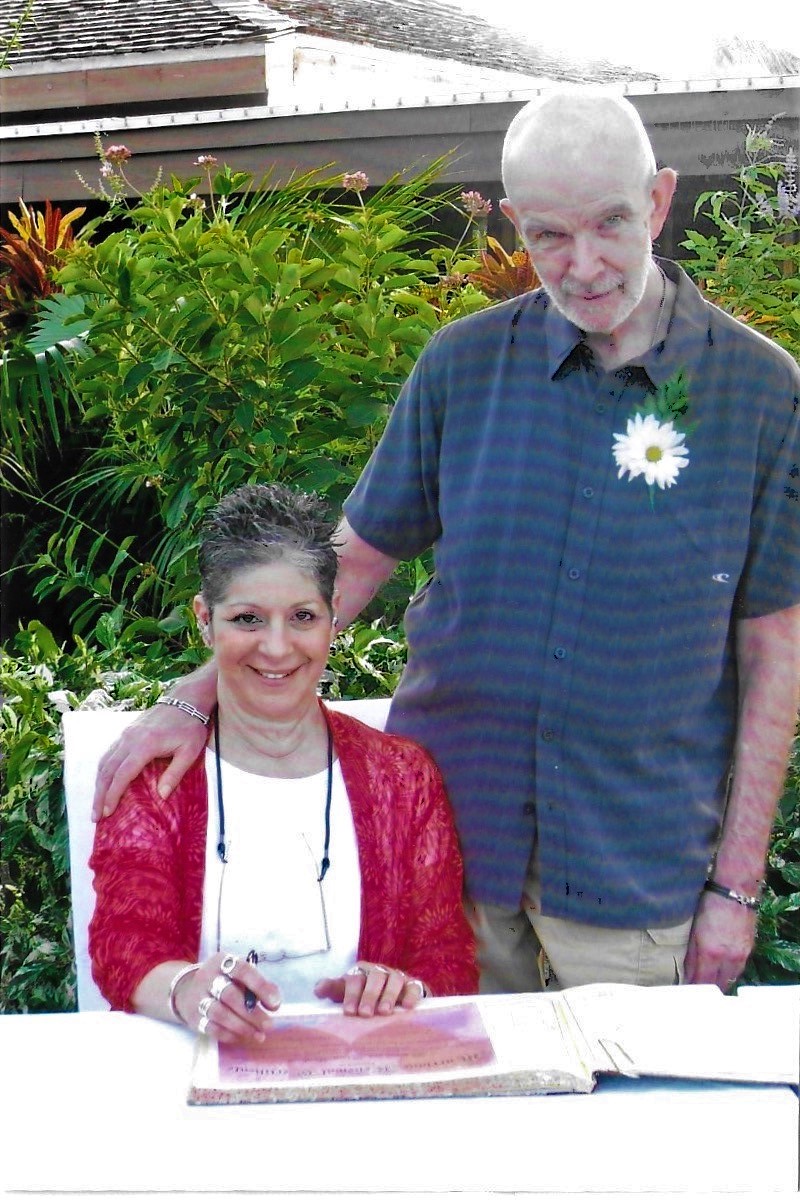

Sidney and Stacey Gibson (courtesy Stacey Gibson)

When Sidney and Stacey Gibson renewed their wedding vows for their twenty-fifth anniversary, they knew their remaining time together would be cut short. Three years earlier, when they were 60 and 55 years old, respectively, Sid had been stricken with spina cerebella ataxia, a rare degenerative brain disease.

As his condition grew worse, Sid explored moving to a state that had legalized medical aid in dying or even going to another country, like Switzerland, but he didn’t want to move away from his friends and family.

Before he died in 2014, the 68-year-old Sid asked Stacey to make another vow: this one to help pass medical aid in dying legislation in New York. She said, “He had been ill for eight long years. He made me promise that I would fight for this law in New York State so that others didn’t suffer the way he did.”

The year after her husband’s death, Gibson, a long-time Garrison resident, became an early champion in New York’s grassroots effort to legalize medical aid in dying. She said, “I was at the very first lobby day in 2015. There was a small band of us who marched on Albany and started knocking on legislators’ doors. I have been at this since then.”

Gibson, a petite and vivacious retired human resources executive, testified in front of the legislature in 2018. She described how Sid’s condition grew slowly and steadily worse, ultimately affecting all of his bodily functions, and how in the end, he opted to stop eating and drinking to end his suffering, dying after twelve days.

She told legislators, “He wanted the option of aid in dying so that he could die in peace surrounded by his loved ones.” She said that, sadly, it was neither peaceful nor beautiful. “The current state of the law forced this death upon him,” she testified.

When Larry Kelly’s colon cancer recurred in 2016, doctors told him he had no more treatment options. Like Sid Gibson had done, Larry explored moving to another state. The 82-year-old widower asked his four children to investigate the possibility of his moving his residency from Michigan to Vermont, a state that legalized medical aid in dying in 2013.

Laura Kelly, a Mount-Kisco-based editorial and website consultant, did the research, then explained to her father that his condition was too advanced, his time was too short, to meet new residency requirements. She has written about the despair and anger she saw on his face. She stated, “He looked at me and said, ‘Too late. Too late.”

Larry had watched his younger brother — his best friend — die of lung cancer with brain metastasis years before. He knew the kind of death he wanted — and which he did not want. Larry, a retired attorney and medical researcher, told his children, “After years of being in control of how I lived, I want to be in control over how I die. I wanted you all standing around me as I died peacefully. Now, I don’t know when it’s going to happen and what I am going to go through.” Speaking of her father, Kelly said, “He wanted to be alert to the end. He said he didn’t want to be a drugged body in a bed.”

Although he received hospice services and medication that helped abate his pain, Kelly said that the 6’4” Larry suffered from a condition known as terminal agitation that was not controlled by medication. “For weeks, he was plagued by restlessness and could not get comfortable nor sleep.” Kelly, now 61 years old, described how the restlessness drove Larry to want to crawl out of bed over and over, and being so ill, he frequently fell. “My poor father kept apologizing about his last days, which weren’t going at all how he envisioned,” she said.

Larry Kelly and his daughter, Laura Kelly (courtesy Laura Kelly)

Kelly had never been politically active until her father’s death. Now, she and Gibson are both volunteer co-team leaders for the Lower Hudson Valley (LHV) Action Team for Compassion & Choices. They, along with other advocates, had hoped to see the New York law pass before the legislature adjourned for the year in late June, but it did not.

Now 70 years old, Gibson said, “We have made remarkable progress, but we are not there yet.”

POLITICAL BACKDROP

The question that is central to the proposed New York legislation is whether mentally competent, terminally-ill adults, who meet other specific medical and legal criteria, should be able to request and receive a prescription medication that they can take to end their life if they so choose.

In 2016, a similar medical aid in dying bill with bipartisan support was approved by the New York State Assembly Health Committee. The bill was reintroduced in 2017 and again in 2021. Over time, there has been growing legislative support, with 68 of the 213 New York State lawmakers now signed on to the bill.

Westchester’s Assemblywoman Amy Paulin is the legislation’s lead sponsor along with Senator Diane Savino of New York City. Paulin said that the pandemic dominated legislative discussions and slowed movement for other initiatives in this year’s legislative session. “Everything turned upside down last year,” she said, adding “This bill is a high priority for me going into next year’s session. I feel we have enough support to see the bill move, if not pass both houses.”

In 2018, a Quinnipiac University poll revealed that New Yorker voters support medical aid in dying by about a 2-to-1 margin (63 to 29 percent) including a majority of both Democrats and Republicans, and across genders and age groups. The exception was that people who attend religious services weekly were opposed by 61 to 34 percent. New York State requires the legislature to pass new laws rather than enactment by public ballot vote.

Corrine Carey is the NY & NJ Campaign Director for Compassion & Choices and is based in New York’s Capital Region. She said, “We have an incredible geographic mix of bill sponsors, some who have been around for a long time as well as newer members.”

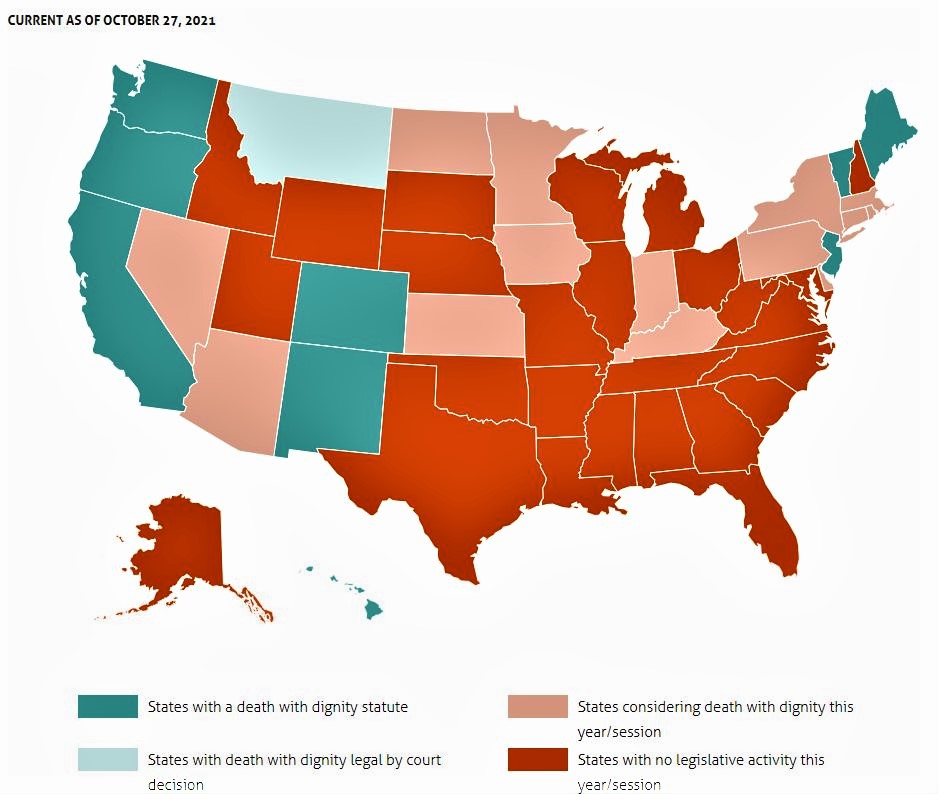

Status of Death with Dignity Legislation by State

(Used with permission from Death with Dignity Take Action – Advocate for Death with Dignity in Your State)

The proposed New York legislation is modeled on laws passed in 11 other jurisdictions — ten states and the District of Columbia. Neighboring New Jersey passed the law in 2019. Oregon is the state with the longest experience with legalized aid in dying, with more than 20 years since the Death with Dignity Act passed in 1997. Carey said that 16 other states are currently considering similar legislation.

Despite the pandemic-related issues being at the forefront of discussions in the last session, Carey said, “Lawmakers are doing their research, having their staffs write position papers on the issue, doing constituent polls on their own, talking to colleagues, and talking to stakeholders in their communities.”

Corrine Carey, the NY & NJ Campaign Director for Compassion & Choices (Courtesy of Compassion & Choices; photo by Shannon DeCelle)

New York Senator Pete Harckham, whose district includes large parts of Westchester, Putnam, and Dutchess counties, is one of the bill’s supporters. He said, “For me, it’s about dignity in dying and patient choice.”

“This is one of those highly sensitive, highly personal bills,” Harckham acknowledged. He expressed his respect for individual personal and deeply-held spiritual beliefs and described differences within his own family. His father, now deceased, was a devout Catholic and presumably opposed to aid in dying; his mother is still living and supports the option. “She witnessed her own mother die a very painful death and she wants to be able to have choice.”

“People say to me, ‘Is this suicide?’ This is not suicide. Sid wanted more than anything else in the world to keep on living; but he was already in the process of dying, his body had betrayed him. All he wanted was to die peacefully, but he didn’t, and that’s just not right.” — Stacey Gibson

Harckham believes that a way to build consensus is for people to understand the bill’s protections. “When people really read the language of the bill, some of the criticisms just don’t match,” he said. “There are a lot of safeguards in the bill, but it takes time for people to learn the details.”

Among the bill’s protections are the requirements that the patient must submit one oral and one written request with two witnesses, be examined by two physicians, and must be able to take the medication themselves if they then choose to do so. This is not the same as euthanasia, or “mercy killing,” which is when lethal medication is administered to the patient by another person, and which is illegal throughout the U.S.

Assemblywoman Aileen Gunther’s district includes parts of Orange and Sullivan Counties. A registered nurse, Gunther acknowledged ambivalence about medical aid in dying legislation. She said, “I do believe that people should die in peace” adding “I believe in a pain-free death.” She said, “My only hesitancy is the self-administration.” She voiced the importance of being able to ensure patients’ mental health capacity in making that decision.

Representative Sandy Galef has held multiple Town Hall style meetings to educate herself and her constituents in northern Westchester and Putnam about the bill’s related issues. She described, “A few years ago, we did a panel with two people in favor and two people opposed to the legislation. We had a thorough discussion. I did a survey and asked attendees about their opinions both before and after the meeting and most people were in favor following the discussion.” She said her own support of the legislation has been a gradual process over the years as she has learned more about the experience from other jurisdictions that have passed the law and of the bill’s safeguards.

CONCERNS AND CONTROVERSY

David Leven, a 78-year-old Pelham resident, has been at the forefront of patient end-of-life issues since 2002, first as the former Executive Director of End of Life Choices New York and now an Executive Director Emeritus of and Senior Consultant to the organization.

As an attorney, Leven has long-held roles that advocate for social justice. He said, “The issue here is health justice, including medical aid-in-dying, to ensure that people have rights to all options to be able to have the best death possible.”

Pelham resident and former executive director of End of Life Choices New York David Leven (courtesy End of Life Choices New York)

Some people object to medical aid-in-dying based on their religious or moral beliefs. Opponents, and even some supporters, refer to the act as assisted suicide, which has powerful emotional connotations. The proposed legislation specifies that “self-administering medication under this article shall not be deemed suicide for any purpose.”

Gibson said, “People say to me, ‘Is this suicide?’ This is not suicide. Sid wanted more than anything else in the world to keep on living; but he was already in the process of dying, his body had betrayed him. All he wanted was to die peacefully, but he didn’t, and that’s just not right.”

In states where it is legal, not everyone with a terminal illness meets the criteria to receive medical aid in dying even if they desire it. And among those who get a prescription that could end their life, reported data across jurisdictions to show that slightly more than one-third, or 36 percent, do not use it. Just having the option may provide a sense of comfort or a “safety valve.”

Gibson and Kelly acknowledge that they don’t know if their respective loved ones would have taken the medication had the option been available, but they both had adamantly wanted that option.

Kelly said, “One of the things that appeals to me about this law is that it forces the doctor, the patient, and family to all talk about the expectations and their wishes for the end of life before it gets too late, as it did for my dad.”

According to Leven, one of the understandable arguments against the law is that if terminally ill patients were to get good hospice and palliative care, medical aid in dying would be unnecessary. He noted, however, that data shows that more than 85 percent of people who use the legal prescription to end their lives were receiving hospice services when they died.

Leven said, “There have been no serious efforts to repeal any law in any state because the laws have worked as intended.” He added, “The problems that were expected by opponents have simply not emerged.”

THE ROAD AHEAD

Carey was at the helm of the campaign that helped pass New Jersey’s medical aid in dying law two years ago and remains optimistic about the pending legislation in New York. “Once this bill passes — and I have no doubt that it will, it’s just a matter of when — nothing changes for people who do not believe in medical aid in dying. Everything changes for a terminally ill person who struggles to find peace at the end of life.”

It is often personal experiences that prompt people to activism. Paulin noted that sharing personal stories is important to educate New Yorkers. It can help people empathize about how having a choice for medical aid in dying may affect some future lives–and deaths.

By sharing her own story Kelly explained, “We are trying to help people understand that for a small group of people with a terminal illness, it’s just another option like all the other ones that are available at the end of life.”

Gibson said she continues the work in Sid’s honor. She is a two-time cancer survivor herself, first with breast cancer decades ago and more recently with lung cancer in 2019. She added, “I got very lucky that both were caught early but I know there are no guarantees. I am also fighting for me. I want to know that if things get bad, I have that option.”

Referring to the vow that she made to Sid, Gibson said, “I started in 2015. It is 2021. I will work for this until it is passed.”

Sherrie Dulworth is a lower Hudson Valley freelance writer whose stories range across healthcare, careers, literature, and human interest. She often finds tranquility with her nose in a book or her feet on a hiking trail, but not simultaneously.

We hope you’ve enjoyed today’s section of Examiner+. We love honest feedback. Tell us what you think: examinerplus@theexaminernews.com

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.