Banning the Holocaust

News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

My great uncle Carl’s story is one of more than six million reasons to push back on school district-sponsored censorship.

Good evening. We hope you enjoyed this morning’s story on Westchester’s post-pandemic real estate market. Today we are proud to present our subscribers with a second, “bonus” story — and it is indeed a bonus, coming from such a gifted writer as our Publisher, Adam Stone. Adam felt compelled to put proverbial pen to paper in response to a Tennessee school board’s head-scratching decision to ban a popular and lauded book about the Holocaust from its curriculum and school library — compelled because the Holocaust irrevocably touched his family’s life. With tens of millions of civilians killed by the Nazis — six-million Jews and millions of others, including non-Jewish Russians and Poles, those with mental and physical disabilities, European Roma (Gypsies), and LGBT individuals — Adam’s story, tragically, is not a unique one. But all the more reason why the actions of this school board are so shocking and serve as a cautionary tale. In an era of fake news where our citizenry can’t even agree on who our lawful president is, the specter of Holocaust denialism is bound to rear its abominable head.

Robert Schork, Digital Editorial Director

Need to subscribe — or upgrade your Examiner+ subscription?

Join the community as a full-fledged member with our special FREE TRIAL OFFER for the New Year: Enjoy 30 days of total access to Examiner+ for no charge. Offer expires at month’s end.

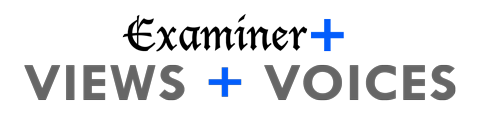

Claire was a young woman in love, with her whole life in front of her, a life with her handsome fiancé, her future husband, and presumably their future children.

But then it happened. The unthinkable happened.

Her fiancé Carl (Karoly in Hungarian) went missing. It was 1943 in Budapest. Hilter and the Nazis and Nazism were killing the Jews.

After Hungary was eventually liberated, in the spring of 1945, Claire would hear stories of Jews who vanished, gone for years, but evaded death during the Holocaust, only to return home, and live a new life.

Hope is a powerful emotion, and Claire (or Klari in Hungarian) would spend the rest of her youth — the remainder of her hope — walking to the nearby local train station, begging God that Carl would reemerge. She’d stand on that Budapest Western Terminal platform waiting and waiting.

“This is Carl, did you by any chance see him?” we were told Claire would ask other survivors getting off the train. She was accompanied by Carl’s desperate mother — my great grandmother — and a photograph of Carl.

But he never returned. He was one of the six million Jews slaughtered by the swords of hate while many of the survivors, like her, were alive but ruined — with generational impact we feel to this day.

Carl was my father’s father’s brother. My father’s uncle. My great uncle.

Born in or around 1914, Carl should have been at my Thanksgiving table growing up, and into my adult life, if only history spun differently and he lived a long life. Same with my paternal grandfather’s other brother, Martin (Marton in Hungarian), who was also murdered in the Holocaust, along with several other family members. Although we don’t know for certain how Carl and Martin were killed by the Nazis, we have compelling reasons to believe they were hosed down and froze to death at a forced labor camp in Ukraine. My father’s father Andrew, my paternal grandfather, was the oldest of the three boys and survived the Holocaust, despite enduring (and later escaping) life in a forced labor camp in Hungary in 1944. He eventually made his way with my grandmother Elizabeth, a fellow Holocaust survivor, here to New York in 1963 following about half a dozen years in Israel — the only country that would take them and my father in 1957. Although Andrew died of cancer before I was born, Elizabeth played a major role in my childhood and young adult life. But I’ll never forget the haunting sadness in her beautiful blue eyes. It took this writing today, all these years later, to fully process the cause and depth of that vivid grief.

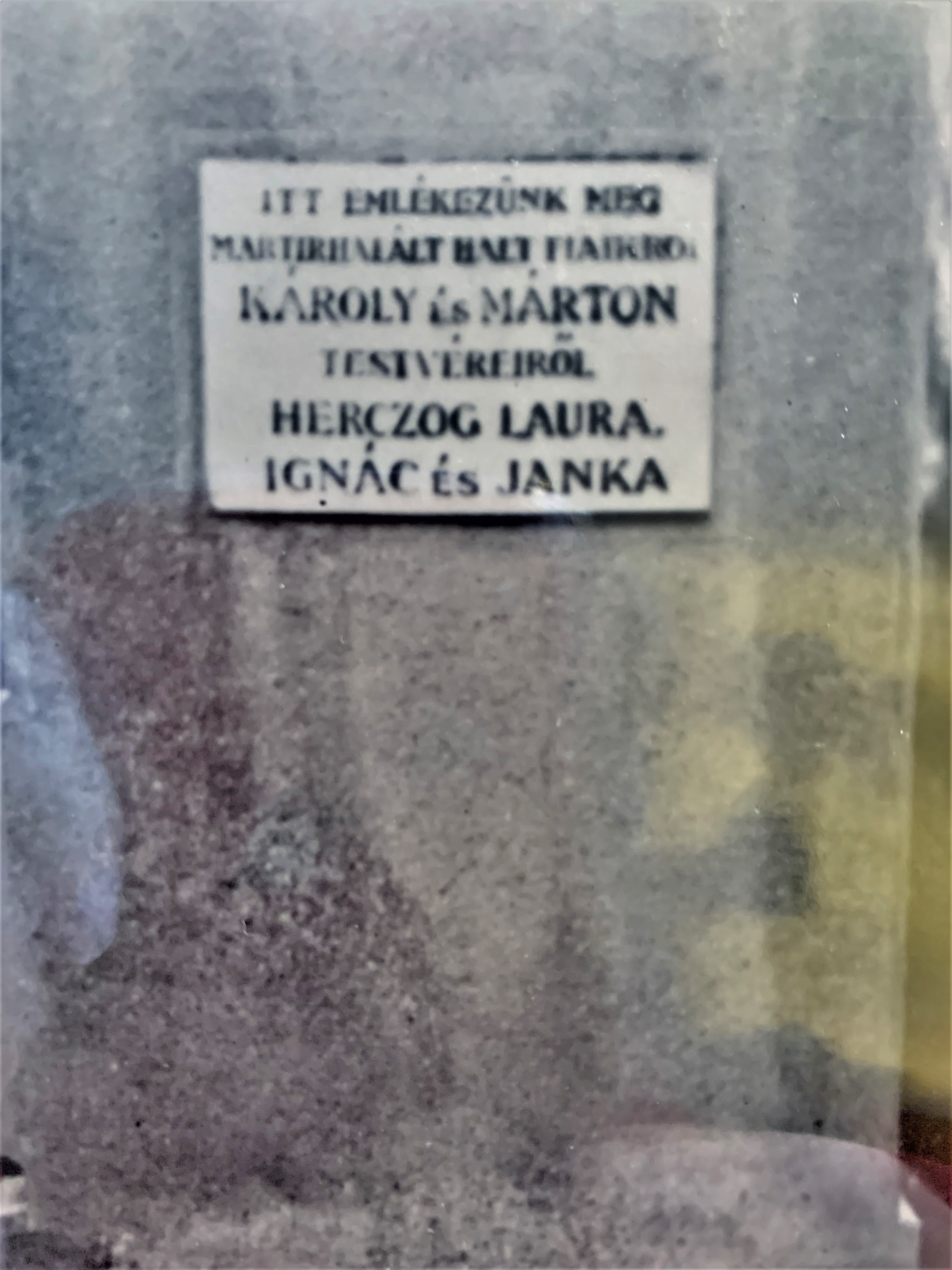

My dad even has a picture of a tombstone in Budapest commemorating the names of those lost to the Holocaust on his father’s side. When he discovered the picture, he was shaken by one of the names on the stone: Laura. That happens to also be my sister’s name, a fact he didn’t know till studying an image he found in a box of loose family photos. The stone is engraved with a memorable inscription, translated from Hungarian to English this way: “We hereby immortalize our loved ones who died the death of martyrs.”

It’s too easy to forget how in the grand sweep of time, the Holocaust remains such recent history, so close we can touch it. And as I type here this morning, Thursday, Jan. 27, on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, the day of this writing, we awoke to the news that a Tennessee school board banned a critically-acclaimed graphic novel (Maus) about the Holocaust.

As far as I can gather, or at least as far as I can generously gather, the school board members acted out of misguided good faith. They claim to support the teaching of the Holocaust but contend this particular Pulitzer Prize-winning book was inappropriate due to perceived vulgarity ill-suited for young people. If we weren’t in this burgeoning moment of book banning, perhaps we could have a more nuanced conversation about a particular book. But it’s impossible to remove this individual decision from the larger context.

With anti-Semitism and broader racial hatred rising in recent years, the disturbing trend in America of book banning brings with it real danger. Granted, school boards can and should help guide curriculum and there are always other books to choose from. But the energy around the emerging book-banning political culture focuses on books that teach children about the world’s real racial problems. And the book-banning proponents will hide behind specious arguments, claiming a little scattered sexual imagery or some salty language might poison the minds of our kids.

Let’s call bullshit.

There’s an honest debate we could theoretically have about how best to educate children on these issues. But the conversation has been profoundly dishonest around so-called Critical Race Theory. Sure, we could and should have a debate over how to, say, teach kids about our country’s sin of slavery at a young age versus more advanced ages and all the rest. But in the world we’re living in, almost any effort to teach students about our ongoing racial challenges gets called into question, and mindlessly and ignorantly characterized as “CRT,” poisoning the entire dialogue and limiting our ability to address any real concerns.

While it’s critical to avoid false equivalencies, it’s also important to highlight how with anti-Semitism in particular, hatred and ignorance is a poison that comes from both the far right and the far left, and then starts to infect the middle. For instance, the vitriol directed at Israel on college campuses causes many Jewish students to hide their identity. And while it’s fine and healthy to critique Israel’s government for one reason or another, the degree to which elite institutions focus on those issues over and above vexing human rights problems in countries all over the world fosters the very atmosphere where American Jews are attacked in broad daylight when violence transpires in the Middle East. And even though it’s important to acknowledge the difference between criticizing the Israeli government and anti-Semitism, there seems to be a monumental knowledge gap on the left about the desire of Israel’s neighbors to see the country wiped off the face of the earth. Let’s face it: that real threat is going to impact policy.

All that being said, it’s undeniable that the most venomous anti-Semitism in this country stems from the far right, through fascist sentiments similar to the brand of far-right ideas that delivered Hitler an ideological marketplace when he was a rising German politician.

And as we get further and further away from the Holocaust, and more and more survivors die off, it’s imperative that we redouble efforts to teach the next generation what transpired.

If preposterous Holocaust-denying ideas can spread in 2022 when survivors remain on this earth, can you imagine how easy it will be to propagate lies when the history becomes harder to see and touch?

I’ll never forget as a college student on Long Island, at Hofstra University, when The Chronicle campus newspaper inserted a Holocaust denier booklet into its pages. It was a paid ad. The editor was well-intentioned, as was the ethics professor who advised the newspaper. They theorized it would be wrong to deny advertising from anyone since newspaper ad departments don’t generally discriminate over the morality of their clients. Sunlight is the best disinfectant and they were just exposing the booklet as fraudulent by distributing it, or at least that was their argument. It was an egg-headed decision, despite the absence of malice, but it’s easy to imagine a college newspaper of the future making a similar decision without even having a rich understanding of the pamphlet’s dangerous lies.

In fact, today’s book-banning champions bathe themselves in this argument, claiming they’re applying the same logic as the people who opposed The Chronicle’s dreadful decision. But comparing the distribution of something like a Holocaust-denying pamphlet, inserted without context in a student newspaper, and condemning the teaching of a Toni Morrison book, is like equating apples and rat poison. Absurd on its face.

In fact, there’s ample room in education to teach books with content we vehemently reject. In a proper setting, having students read and understand Hitler’s Mein Kampf would enhance their education. To assign classroom reading is not to endorse.

One of the most upsetting aspects of this entire issue, for me, is how it feels like a local story. From Facebook pages to school board meetings, the intolerance from some quarters can be palpable in our towns, just as it is in communities across the country.

Thankfully, there’s real reason for hope. The current generation of young people, broadly speaking, are hip to the ignorance of their elders. Not just that, but they’re actively pushing back.

“I’m simply going to say that no government — and public school is an extension of government — has ever banned books and banned information from its public and been remembered in history as the good guys,” a young woman in Texas, a high school student, told the local school board this past Tuesday about its “book review” — an order that would authorize the school officials to ban books from district schools without any public comment.

And as I think back about Claire at that train station less than eight decades ago, I’m struck by how much we owe her. She stood hopefully and stoically and tragically on that platform in post-war Budapest, and it’s important we honor stories of people like her by avoiding the sins of the past.

We owe it to her to remove ourselves from our ideological bubbles. Sometimes content outside our natural comfort zones helps educate and awake the learning mind, even if it contains lurid stories or colorful language. Even if — or especially when — it contains facts that illustrate our complicated, often brutal racial history.

So, in that spirit, and in light of the emerging book-banning culture in America, let’s depart from our cozy media bubbles, and learn real history. Let’s push back firmly on any efforts to falsely sanitize our classrooms. Let’s paint a clear picture to students of the world they are inheriting — and responsible for improving.

Apologies for the F-bomb, but it’s time to wake the fuck up before we condemn the next generation to an F in global studies because of our negligence and ignorance. The history we teach kids must be honest, contextualized, and, yes, uncensored.

Adam Stone is the publisher of Examiner Media. When not running local news outlets or chauffeuring his children, Stone can be found on the tennis courts at Mt. Kisco’s Leonard Park, on his iPad playing chess, or on the floor cleaning after his two dogs.

We hope you’ve enjoyed today’s section of Examiner+. What did you think? We love honest feedback. Tell us: examinerplus@theexaminernews.com

Adam has worked in the local news industry for the past two decades in Westchester County and the broader Hudson Valley. Read more from Adam’s author bio here.