An Unnecessary Cut?

News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

With the 12th highest c-section rate in the country, advocates in New York look at ways to reduce the prevalence of the procedure — especially for first-time, low-risk births

Good morning! Today is Monday, July 18, and you are reading today’s section of Examiner+, a digital newsmagazine serving Westchester, Putnam, and the surrounding Hudson Valley.

Need to subscribe — or upgrade your Examiner+ subscription to enjoy full access to all of our premium digital content? Take advantage of our special FREE TRIAL OFFER.

Take Examiner+ on a test drive today at NO CHARGE for a full month. Enjoy full membership-level access to all of our premium local content, delivered straight to your inbox six times a week.

Today’s presenting sponsor of Examiner+ is Rock White Plains.

There’s no question that a cesarean section (c-section) is a lifesaving, medically necessary procedure in high-risk situations where the health of the mother, baby, or both is in danger.

However, doctors, midwives, doulas, and politicians agree that an overreliance on this procedure — especially for primary, low-risk pregnancies — can cause more harm than good.

In New York State, the c-section rate sits at 33.6 percent, making it the 12th highest in the nation. While the procedure is the most commonly performed surgery in the United States, it is not risk- or complication-free.

Because New York’s c-section rate is well over ideal targets set by both Healthy People 2020 and the World Health Organization — 23.9 percent and 10 to 15 percent, respectively — advocates say bringing these numbers down is critical for the health and safety of birthing parents and babies as well as to improving hospitals’ obstetric culture.

How c-section rates skyrocketed

Across the United States, c-section rates have skyrocketed in the past five decades. Today, one in three babies are born via c-section, a 500 percent increase since the mid-1970s. Many factors have led to these rising numbers, and the answers depend on the vantage point of the person you ask.

Experts believe that technological advantages, particularly fetal monitoring, can raise more alarms during labor. Continuous monitoring, which tracks a baby’s vitals as soon as a pregnant person enters a hospital, has become a standard of care despite extensive research on interpreting these readings.

For example, if a baby’s heart rate goes up or down, it can trigger a c-section (despite not knowing if the baby is actually in distress).

Often, pregnant individuals are told they’re carrying babies deemed too large to be delivered vaginally, which leads to c-sections. However, fetal weight measurements are frequently inaccurate, sometimes with an error of more than 10 percent compared to the actual weight.

Different hospitals and obstetricians also have different opinions on how long a pregnant person should spend pushing before they get a c-section, as well as how long after the water breaks they should be allowed to try for a vaginal birth. Often, the cutoff time is completely arbitrary.

Joyce Havinga-Droop, a holistic doula who runs Birth Ambassador, has attended hundreds of births throughout Westchester, Rockland County, Connecticut, and New York City.

With over a decade as a doula, she believes an over-medicalization of childbirth in the United States is an overarching symptom that has led to higher c-section rates, particularly for low-risk pregnancies. Rather than viewing birth as a physiological event, Havinga-Droop says the majority of obstetricians see it as a medical event where interventions are necessary.

“Most of pregnant people’s care in our area is being handled by obstetricians,” Havinga-Droop says, explaining that much of their surgical training is about handling high-risk pregnancies and maternal or infant emergencies during delivery. “If you have like 90 percent of your population being seen by these highly trained doctors, of course, their specialty is to go into surgeries, and that’s where the [medical] system goes wrong.”

Havinga-Droop, originally from Europe, says that the United States is an outlier compared to other industrialized nations that have a midwifery model of care.

“The model of midwifery really supports the woman leading in what she wants and what the atmosphere should be,” Havinga-Droop says. “When you move into the medical model of care, all of that is stripped away from you.”

Helena Grant, Director of Midwifery Services at Woodhull Hospital in Brooklyn, highlights that there is indeed a disconnect between the care that low-risk pregnancies actually need and the medical interventions with which they’re often met.

“Physicians approach childbirth as something that needs to be manipulated with and not let be even when it can be,” Grant explains. “Obstetricians are surgeons, and I personally love having them around when I need them. But when they’re not needed, they’re not needed.”

“Because they have the expertise in surgery, it becomes a part of their subset of skills that they go to, a lot of times, prematurely,” Grant adds. “When it comes to Black women, in particular, the [c-section] rates and disparities are extremely high.”

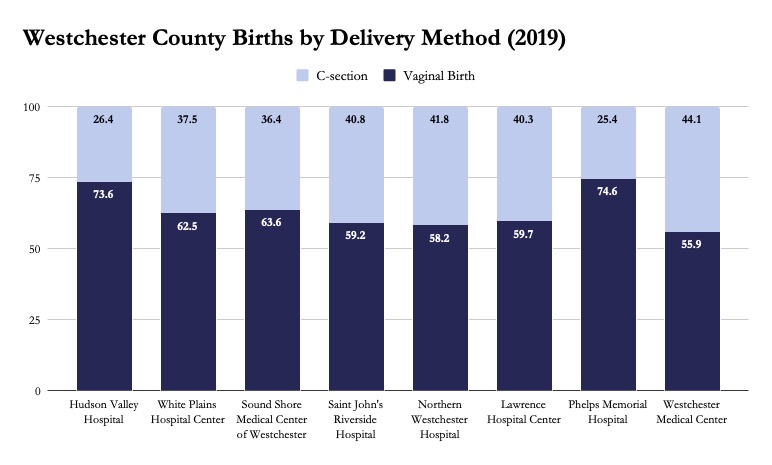

According to data published by the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH), Phelps Memorial Hospital in Sleepy Hollow and Hudson Valley Hospital in Cortlandt Manor had the lowest overall c-section rates of all Westchester hospitals in 2019 at 25.4 percent and 26.4 percent, respectively. Other area hospitals have rates in the high 30s to low to mid-40s.

NYSDOH does not publish data detailing how many of the total c-sections were for low-risk births.

Additional factors at play

Ease of scheduling deliveries and higher insurance payouts also play a role in whether an individual will ultimately have a c-section.

“If you can come in and hurry up and manipulate somebody’s labor or call a c-section, you can get back to your office or get back to your family,” Grant explains. “It’s not about supporting this beautiful process anymore.”

According to data compiled by the Health Care Cost Institute, the median payout for a c-section in the New York greater metro area was $13,830 compared to $9,875 for a vaginal delivery.

“[C-sections] exponentially increase capital for the doctors doing it and the hospitals,” Grant adds. “That’s why the hospitals are not really holding providers accountable.”

At Nur Midwifery, Nuranisa Rae, a home birth midwife, serves Westchester, Rockland, the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens. Previously, Rae spent seven years as a labor and delivery nurse at a hospital in New York City.

She said from her time working in the hospital, there was a definite increase of c-sections around 4:00 p.m and 10:00 p.m., which, to her, revealed a culture of doctors who don’t want to be up all night or have dinner plans.

“It’s nice when you don’t have to be up all night, but you don’t become an OB-GYN or a midwife for the schedule,” Rae explains. “I think [providers] try to fit births into their lives instead of fitting your life into birth.”

Rae also notes that doctors’ fear of lawsuits is a factor that impacts c-section rates as well.

“If you let someone labor long enough and God forbid something happens, in a court of law, you’d always be blamed for not c-sectioning them quick enough,” Rae says. “But if you just c-section them, then you can say, ‘Well, I did everything I could.’”

“In a court of law, it doesn’t benefit you to wait, and that’s constantly where the thought process of doctors is,” Rae adds.

Additionally, Rae notes that in teaching hospitals like the one she worked in, residents need to get a certain amount of training on various delivery interventions. As a result, things like a forceps delivery may be framed to a person in labor as medically necessary when, in actuality, it may be to aid the residents’ training that day.

Rae says she witnessed these procedures be practiced on patients who came from the hospital’s clinic population, which had a majority of Black and brown patients.

“There were a couple of times where people were having normal births, and it was like a Tuesday when the attending who was really good at forceps was going to teach the resident that day how to do forceps,” Rae recalls. “So they pretty much lied to her, scared her into believing that the baby was not doing well, and didn’t give her the opportunity to push.

“People are taken advantage of by [doctors] saying ‘We have to do these things because you want your baby to be safe,’ and informed consent doesn’t really happen,” Rae continues. “We often talk about how the whole maternal health system is totally racist. This was the first time it was so blatantly obvious.”

Today’s supporting sponsor of Examiner+ is Manhattanville College.

Grant underscores that the impact of medical racism and the historical manipulation of Black women’s bodies, especially in the field of obstetrics, continues today.

“It started out with experimentation on plantations. Now we end up with these c-section rates in hospitals, and women coming out and saying, ‘This was done to me,’” Grant says.

Unnecessary c-sections, increased risks

Dr. Angela Silber, Chief of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at Westchester Medical Center (WMC), is an obstetrics specialist who often deals with high-risk, complicated pregnancies — many of which are transferred from other hospitals in the region to WMC.

In a high-risk delivery situation, she says she can always comfortably walk away, knowing the c-section saved the life of the mother and baby.

“But when we’re talking about a low-risk patient — no medical morbidities, a normally growing term pregnancy with a baby positioned head down — cesarean delivery does pose a higher risk of complications than a vaginal delivery,” Dr. Silber explains.

Mothers who undergo c-sections are more likely to suffer from complications such as the increased risk of infections, hemorrhages, extreme blood loss, anesthetic complications, and organ damage.

A report published by the NYSDOH in 2018 found that the pregnancy-related death rate for c-sections was 1.7 times higher than that of vaginal births — a number that increases exponentially in Black and brown communities.

In the long-term, Dr. Silber explains, a c-section can also impose risks for future pregnancies.

“Once you have one c-section, if you have a second or third c-section, that scar tissue makes the surgery more risky and increases the risk of placenta accreta, where the placenta, due to scar tissue on the muscle of the uterus, grows into the muscle layer,” Dr. Silber notes.

“That can become a very complicated surgery and requires somebody to have a hysterectomy,” Dr. Silber adds. “You can’t remove the placenta after the baby is born. You have to remove the uterus [too].”

Because the majority of hospitals across the state do not offer vaginal birth after a c-section (VBAC), a primary c-section creates a domino effect.

Experts agree that preventing the first c-section is necessary to bring down c-section rates overall. Despite this, Grant explains, there are very few hospitals and providers throughout the state who will offer VBACs.

“If you have multiple c-sections, we’re going to have to cut through all that scar tissue, you’re going to bleed more, which is going to increase your risk of infection and recovery time, and you’re going to be in more pain,” Grant highlights. “Why are we not giving women in New York State who choose to childbear this information?”

“We need to be ensuring that VBACs are widely offered as an option for a second birth because once you have two cesareans, there are very few hospitals that will even support a birthing person to have a vaginal [delivery],” Grant adds. “If we miss that opportunity the second time around, it’s completely lost.”

In addition to potential medical complications, a c-section for a low-risk birth can also be a traumatic experience for mothers, particularly if their labor was cut off prematurely for not progressing fast enough.

In a 2019 study of over 2,000 American women published in the medical journal Reproductive Health, one in six reported that they’d been mistreated during childbirth, including feelings of a loss of autonomy.

That rate was found to be substantially higher among those who had unplanned c-sections. The study found that women of color experienced higher rates of mistreatment compared to white women.

“We’re not listening to women, and I think that very much is the problem in the medical system,” Havinga-Droop says.

Additional interventions and oversight needed

In 2014, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine released guidelines on how to safely prevent a pregnant person’s first c-section for low-risk births. Among the recommendations are increased patience from providers and longer labor times.

According to the recommendations, individuals giving birth for the first time should be allowed to push for at least three hours. If epidural anesthesia is used, they can push for even longer.

Additionally, early labor should be given more time, with the start of active labor redefined to cervical dilation of six centimeters rather than the previous four.

Dr. Silber says more flexibility in the labor times considered “normal” will improve c-section rates. Intrapartum support, where a doula or labor nurse can help to reposition the baby or patient, can also aid in the progression of labor, Dr. Silber notes.

Grant believes mandates and additional governmental oversight are both necessary to get New York’s c-section rates down.

“The state [c-section] rate that gets reported does not divide it out, and I think that’s problematic,” Grant explains. “We need state legislation that mandates hospitals to report on a yearly basis its primary c-section rate, repeat c-section rate, episiotomy rates, and third- and fourth-degree laceration rate.”

Additionally, Grant would like to see a central database that details which hospitals have midwives on staff, as well as more insight into the staff on the labor floor.

“We have a problem, and we’re not even offering the general public solution-based information to be able to deal with it,” Grant notes. “All of these are deeply important to allowing the issue of birth equity to be uplifted.”

Advocates also believe Gov. Kathy Hochul should work to remove strict statewide regulations, which make it difficult for midwife-led birth centers to operate across the state.

Legislation introduced

In Westchester, Assemblywoman Amy Paulin (D-88) has sponsored four bills that seek to address the extremely high rate of c-sections in New York State.

“As a mother of three, I know first-hand how much we rely on our medical professionals for guidance and support throughout the pre-and post-natal process,” Assemblywoman Paulin said in a written statement to Examiner+. “As a citizen and lawmaker, I want to ensure that every expectant mother has access to the quality care and detailed information so that they can make the best decision regarding their birthing process and outcome.”

Among the four bills, they would require hospitals and birthing centers to provide five years of data surrounding procedures such as c-sections and episiotomies; establish a cesarean birth review board to study and reduce c-section rates while protecting maternal health across the state; encourage physicians and midwives to complete risk management courses that urge them to have evidence-based discussions with patients about different options for labor and delivery, along with the associated risks; and require hospitals to provide expecting mothers with consistent, accurate information on the risks of cesarean deliveries.

While the bills did not pass during the 2021-2022 legislative session, which ended in early June, Assemblywoman Paulin says she’ll continue advocating for this critical legislation.

“Women deserve to have access to quality reproductive care that does not put them at unnecessary risk of death or long-term health consequences,” Assemblywoman Paulin said. “Expecting mothers should feel safe and in control before, during, and after giving birth.”

Bailey Hosfelt is a full-time reporter at Examiner Media, with a special interest in LGBTQ+ issues and the environment. Originally from Connecticut and raised in West Virginia, the maternal side of their family has roots in Rye. Prior to Examiner, Bailey contributed to City Limits, where they wrote about healthcare and climate change. Bailey graduated from Fordham University with a bachelor’s in journalism and currently resides in Brooklyn with their girlfriend and two cats, Lieutenant Governor and Hilma. When they’re not reporting, Bailey can be found picking up free books off the street, shooting film photography, and scouring neighborhood thrift stores for the next best find. You can follow Bailey on Twitter at @baileyhosfelt.

Examiner Media is a proud participant in The Trust Project.

CLICK HERE to review our best practices and editorial policies.

This piece is a news article. CLICK HERE to learn about our definitions for types of stories.

We welcome corrections, story ideas, and general feedback. CLICK HERE to use our actionable feedback form.

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.