‘What Are We Truly Teaching?’: Why High School Baseball Umpires Are Vanishing in Westchester

Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

By Toby Rosewater

Examiner intern and Managing Sports Editor for The Amherst Student

I first spoke with Dave Greiner, the treasurer of the Westchester County Baseball Umpires Association (WCBUA), over the phone in late June.

Greiner, cruising down the freeway to the glitzy sound of Frank Sinatra’s “All My Tomorrows,” had agreed to speak with me to discuss murmurings of an umpire shortage affecting high school baseball in Westchester.

“The shortage is the biggest problem facing us right now,” he bemoaned. “We have about 114 umpires…we need 180.”

Echoing this concern, Adam Lodewick, the athletic director at Fox Lane High School, recalled that last year, the onerous shortage frequently led to rescheduled matches, canceled games, and mounting frustration among players and coaches.

“It’s definitely gotten worse,” he said. “I don’t remember it ever being an issue when I first started.”

The Times They Are A-Changin’

Greiner, now 61, graduated from Valhalla High School in 1981. He has coached on and off for decades and has spent more than 40 years umpiring Section One athletics.

In that time, Greiner notes, the profile of the typical umpire has changed almost entirely.

Back in the late 1980s, most high school officials were teachers, taking up umpiring as a way to supplement their income and remain involved in athletics. Today, that’s all but disappeared, in part because teachers may no longer need the extra money.

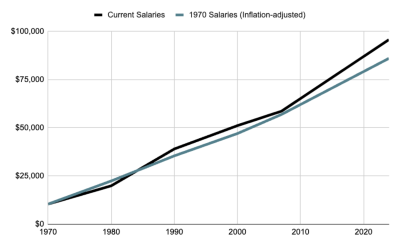

In fact, New York’s average teacher salary of $95,615 is approximately 11.3 percent above what the statewide average would be if 1970 salaries had simply kept pace with inflation ($85,908), indicating real wage growth over that period.

“Schools, you know, really want teachers to focus and concentrate on their pedagogy,” Marco DiRuocco, the head coach of Harrison Baseball and the president of the Coaching Association, said.

This shift in priorities, coupled with higher salaries, means teachers now have other, often more flexible, ways of earning income.

“Instead of getting hot and sweaty officiating games for two hours, it’s easier to tutor for an hour and make just as much,” Greiner said. “The reality is, officiating just isn’t as attractive as it once was.”

The Cost of Doing Business

While teacher pay and shifting priorities have narrowed the pipeline, several other challenges — financial and otherwise — continue to make umpiring a less appealing prospect for new recruits.

Danny Spolansky, a former varsity baseball player at Fox Lane, part-time umpire, and an incoming freshman at Indiana University, spoke with me about some of these challenges.

“One thing a lot of people don’t realize is that you have to buy all your own gear up front,” Spolansky said. “That’s fine, but it can get pretty pricey.”

For Spolansky, the total cost of equipment came to around $500, even after opting for the most affordable options and beginner kits. He pointed out that for many, outfitting yourself as an umpire can easily run even higher, sometimes reaching as much as $700, depending on the quality and type of gear chosen.

For those hoping to umpire high school games, that initial investment is only the beginning — additional fees for certification, training, and annual dues quickly add up.

There’s a $150 fee for the certification class, which includes the first year’s membership dues ($20 for the class itself and $130 for the dues), plus another $100 required for fingerprinting to be cleared as an official in New York State.

Further, for non-certified teachers looking to coach, the expenses are even steeper, sometimes reaching several thousand dollars just to complete the necessary certification courses.

When I asked Lodewick whether Fox Lane would consider offsetting these costs for Section One officials, he made it clear that such support was unlikely.

“I don’t think that would be our school’s responsibility,” he said. “It would be up to the individual who wants to become an official or the Officials’ Association, which could maybe offer a coupon or something.”

Greiner, however, disagrees. He believes schools — and the athletic programs that depend on a consistent supply of umpires — should be more proactive in helping with recruitment and supporting newcomers.

“It’s the schools who pay us — we work for them,” he explained. “If schools require all this certification to allow us on the field, then they should share some of the responsibility for making it possible.”

The Same Rope?

Beyond minor disagreements, there also seems to be a broader, growing separation between officials, players, and coaches.

“One of the reasons people are more hesitant to get into umpiring now,” Greiner told me, “is that, even at the higher levels, the relationship between umpires and coaches and players is often painted as adversarial — like we’re on opposite sides, rather than all pulling at the same rope and working together to make the game the best it can be.”

Greiner points to professional baseball as the main source of this dynamic, citing viral confrontations between players and officials. Locally, the absence of “referee teachers” has undoubtedly played a role in catalyzing this shift.

To address this, some educators have argued that more fully integrating umpires into the educational environment could help rebuild crucial relationships and foster a stronger sense of community on the field.

“Baseball is an extension of the school day,” DiRuocco said. “That’s where some great teaching goes on beyond the classroom after three o’clock. Educators, I think, see the big picture and make great umpires.”

But DiRuocco’s view — of umpires as coach-like figures, playing an important part in students’ learning and personal growth — has become increasingly uncommon.

Without referee teachers, most educators never even consider becoming umpires. This critical distance has deepened the divide between officials and schools. Despite their rigorous training, umpires are not seen as integral members of the educational community, unlike coaches.

This has not only created a permission structure for players and coaches to mistreat officials, but has also stymied efforts to remedy the shortage.

‘Pie in The Sky’

Take, for example, efforts surrounding pension benefits.

In New York, compensation earned from coaching school-sponsored athletics is considered part of a teacher’s total salary for pension purposes. This means that the stipends teachers receive for coaching are factored into their official earnings, which ultimately increases the amount calculated for their pension upon retirement.

The thought is, then, that if a similar policy were applied to officiating, teachers might once again view umpiring as an attractive and practical component of their professional life.

“I, to be honest with you, I like the idea,” DiRuocco said. “I think umpiring is very similar to coaching — they both have a huge effect on our game and on sports overall. To have something like that connected could make a real difference.”

Even with some support, the idea has faced both fierce opposition and bureaucratic roadblocks.

“Some teachers push back,” Greiner explained. “They’ll say, ‘Why should umpiring count toward your pension when my tutoring or other after-school work doesn’t?’ They don’t see it as the same kind of contribution to the community.”

Implementing such a change would demand the buy-in of numerous teachers’ unions, likely require action from the New York state legislature, and necessitate renegotiating a patchwork of existing contracts.

“For something to count as compensation that is pensionable, it has to exist in the teacher’s contract for that school district,” Joseph Vaughan, president of the Scarsdale Teachers Association, said. “You’d have to get dozens of teachers’ unions to agree that they want this — and that’s a very low priority in contract negotiations.”

“Frankly, it’s really pie in the sky,” Greiner concluded.

The Death of Something

Beyond the pension plan, other possible solutions include restructuring modified sports and reforming the certification system, both of which are far, far from becoming a reality.

If none of these solutions are adopted, and this problem is not remedied, youth baseball in Westchester will continue to suffer from random cancellations, delays, and understaffed games.

Sadly, it feels as if we are witnessing the death of something – an era of amateur athletics supposedly isolated from the rat race of the pros, where the sole purpose of the exercise is to grow and learn from those involved in the game.

Instead, we seem to be going somewhere more standoffish. Where wins and losses determine lessons learned, and officials are mere service providers — cogs in the machinery rather than stewards of the game.

It’s funny how things work like that, in a world with sports betting rampant, where illegal parlays are submitted in school bathrooms from Nevada to New York, from Somers to Scarsdale, the ritual of high school baseball — once a cornerstone of community and character-building — now feels increasingly transactional.

“Mutual respect is something that has waned,” Fox Lane High School baseball coach Matt Hillis told me. “I would love to see that mutual respect come back because, in the end, what are we truly teaching?”

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.