Growing Old on Usonia Road: The Honest Reflections of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Last Living Customer

News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

By Toby Rosewater

Seventy-five years ago, a naive and bold Roland Reisley, then 26, sent a letter to Frank Lloyd Wright, the great American architect.

The five-page letter was an attempt by Roland and his wife, Ronny, to define themselves, their $20,000 budget, their needs, interests, and desired lifestyle.

In 277 words, they hoped to persuade the 83-year-old architect to design their new home in Usonia, an experimental cooperative living community outside Pleasantville.

“We do not like compact, massive structures but prefer a sense of lightness and mobility,” he wrote in closing. “We both enjoy books, people, theatre, children, art, music, food, wine, pets, stone, wood, sunlight, grass, glass, sky, and trees.”

Their effort, in short, was a massive success. Over the next decade, Wright not only designed their dream home but also became close friends with the couple, changing the course of their entire lives.

A New Correspondence

A few weeks ago, I found myself, an eager 19-year-old reporting intern, in a remarkably similar position.

After hearing about Roland Reisley’s story through Examiner Publisher Adam Stone, and obtaining his contact information through Stone’s mother-in-law, who regularly plays bridge with Reisley’s current partner, Barbara Coates, I decided to call the 101-year-old’s home phone to ask him for an interview.

“Why don’t you send me an email?” he said. “We’ll try to find a time.”

Within the hour, I carefully crafted my pitch, sent the email, and patiently waited for a response.

Three days later, he got back to me.

“How about Wednesday, August 6 at 2 p.m.?”

“That’s perfect!” I wrote back, “See you then!”

The Usonian Dream

Before the Reisleys ever called it home, Usonia itself was a vision as bold and unconventional as any building Frank Lloyd Wright ever built. Conceived in the early 1940s, Usonia was a collaborative experiment — part idealist dream, part architectural rebellion — founded by a group of young New York City professionals who, in the shadow of World War II, yearned for a different way of living.

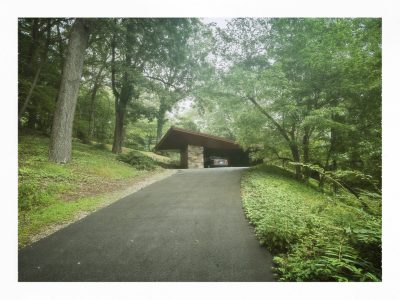

Under Wright’s guidance, the community took shape on nearly one hundred acres of rolling, wooded land, with circular plots, winding roads, and strict devotion to low, open homes of wood and stone, designed to foster harmony with the natural world.

Today, there are 47 homes in Usonia, three of them designed by Wright, including the Reisley House, completed in 1952.

Beginnings

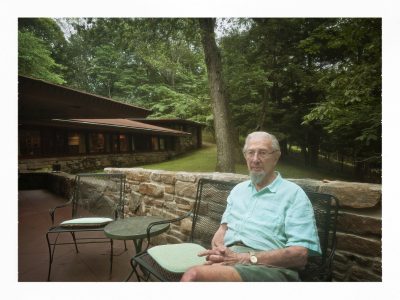

I interviewed Reisley for three hours at his home in Usonia. The setting was every bit as beautiful as promised.

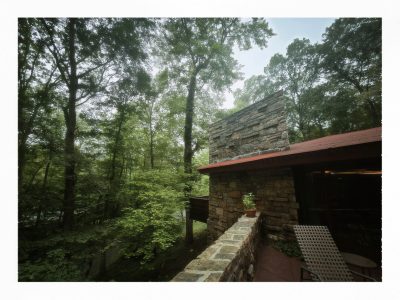

The house rises gently from the wooded hillside, its low, horizontal lines and rough-hewn stone bricks blending seamlessly into the American forest.

Inside, built-in bookshelves, carefully crafted wooden surfaces, large windows, and a monumental stone fireplace convey a warmth and intimacy that is unmistakably human, yet dignified and genuinely sublime.

“Take a seat,” he told me, gesturing toward a Danish-style chair by Robsjohn-Gibbings — one of Wright’s less-fancy favorites. “It’s more comfortable than it looks.”

Reisley’s Frank Lloyd Wright

Reisley has long sought to dispel what he sees as a fanciful image of Wright that persists in the public consciousness.

“Most people who think they know anything about Frank Lloyd Wright are convinced he was arrogant and egocentric,” he said. “But my experience was nothing like that.”

Instead, Reisley claims, Wright was kind, humble, and receptive.

When Reisley asked for more bookshelves, Wright did it. When he asked for more built-in furniture, Wright did it. And when he asked for a darkroom, a workshop, a laundry room, a wine-cellar, and a long sink in the bathroom, every time, Wright did it.

Whenever Reisley raised a new request, he recalled, Wright would say, ‘Roland, you’re my client and I’m your architect. I’ll redesign your house as many times as I need to, just speak up.’”

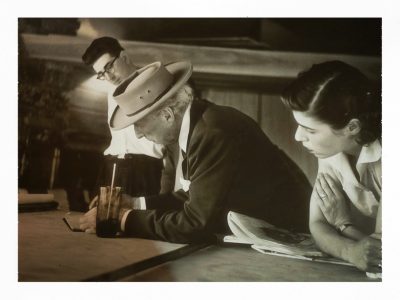

The Reisleys met with Wright approximately 10 times during the construction of their home, once at Taliesin West (Wright’s Arizona studio), four times at the construction site, and the rest at the Waldorf Astoria and the Plaza Hotel in New York City.

Even after their working relationship ended, Wright continued to invite the Reisleys out to events and building sites, cementing a friendship that lasted until Wright’s death in 1959.

“He became a real mentor and a true friend,” Reisley said. “I was sad when he died, but more so than anything, I felt lucky to have known him.”

Seventy Years of Shelter

As Reisley showed me around the house, I realized how little the place had changed over the past seven decades.

There’s a rectangular hole cut into the side of the chimney where a small, plasma television resides — that’s new. And the original kitchen countertop, once battleship linoleum, is now red Formica.

“My home hasn’t changed much,” Reisley laughed. “And I don’t imagine it will — unless, of course, I decide to invest in a large flatscreen.”

At the same time, Reisley says, his home hasn’t been plagued by the same maintenance troubles that often bedevil older buildings, particularly those of Wrightian design.

The cypress wood near the entryway has been waxed only once (30 years ago), the concrete floor doesn’t require sanding or varnish, and nearly all of the furniture remains original.

“Look at this,” he told me, pointing to the top of a waist-high bookshelf in the hallway, where an old, mammoth-sized dictionary sat, splayed open like a bible.

“They say not to throw away your dictionary,” Reisley explained. “It’s true — a real dictionary tells you more about a word than anything online.”

So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright

“Last living” carries a kind of magnificent implication, so much so that I think we often forget the tragic reality of the phrase.

Reisley has outlived most everyone he’s ever known.

That includes two of his children and his late wife, Ronny, who died in 2006.

“Ronny and I were seen as a unit, as an entity,” he said. “When she died, it hurt for a long time. It was hard to live here without her. It changed the space, but I can’t really articulate the difference.”

On top of this, Reisley misses the little things, too.

Just down the hill sit two, often vacant, community tennis courts.

In Usonia’s early years, the community had about 12 or 13 active tennis players, including Reisley, who would often get together and play.

“Nobody cared about who was good or who was not so good. We just enjoyed playing together,” Reisley said. “It was a great time.”

Nowadays, though, people often play elsewhere, and the courts are usually empty.

“I try to encourage our Usonia tennis players to get together more, for the community’s sake,” Reisley said. “I’m not sure it will happen. That sense of connection, I think, is long gone.”

I find this particularity fascinating. While Reisley’s house is significant — and it is beautiful — what has made the whole Usonia experience remarkable, at least for Reisley, is not exactly the revolutionary architecture, or his proximity to an American titan, but something that, on paper, is much more attainable.

“Usually, you know, people only want to talk about what it was like to work with Frank Lloyd Wright — and that’s a whole other interesting conversation,” Reisley said. “But really, that’s just a subset of what’s important here. The community, I think, has always mattered most to me.”

New Attention for an Old Story

As Reisley has grown older, and his story has gone from one of many to the very last, it has become clear that the world is now more interested in the 101-year-old than ever before.

In the past half-decade alone, Reisley has been interviewed by The Wall Street Journal, Architectural Digest, ABC, BBC, and most recently, NPR.

“People recognize Frank Lloyd Wright’s name, but few know much about him,” Reisley said. “I think people are intrigued by the human story. Who was this guy? What were his ideals? And frankly, what did he try to build here?”

In many ways, Frank Lloyd Wright, in all his forms, represents a utopian vision of America.

For those of us — like me — born long after his death, he exists somewhere between myth and memory, a totem of American creativity whose name endures even as our sense of shared culture disintegrates.

In that sense, to spend an afternoon with Roland Reisley, who once exchanged handwritten letters with Wright the way I swap text messages with friends, is to touch a now-vanishing thread that connects us to a more idealistic — if equally flawed — version of our national story.

“I never get bored sharing my home or Wright’s ideas,” Reisley concluded. “I like to think I’m spreading awareness, like Johnny Appleseed. To me, that’s all that really matters. I’m just happy to keep it going.”

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.