Ice (Cream) Castles

News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

How a flat tire in Hartsdale led to Tom Carvel’s multimillion-dollar ice cream empire — and a complicated legacy.

Good morning! Today is Monday, August 22. You’re reading today’s edition of Examiner+, our bonus content newsletter for members.

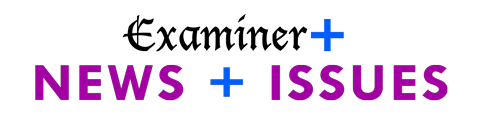

It all started on Memorial Day weekend in 1934. Greek-born American businessman Athanassios Karvelas, better known as Tom Carvel, was driving an ice cream truck when he got a flat tire. He pulled into a parking lot next to a Hartsdale pottery store and began to sell the melting ice cream to people passing by.

As he sold the ice cream from the parking lot, Carvel got the idea that perhaps he didn’t need to drive the truck from one location to another after all. If he could set up shop in one spot — and figure out a way to replicate the partially-melted soft ice cream that became the accidental product of his flat tire — he could increase his profits.

The store’s owner graciously allowed Carvel to use electricity from the store, so he decided to come back and sell from the same place. Within two days, Carvel sold his entire supply and came to the conclusion that a fixed location would indeed set him up for success.

“He discovered people liked it, took advantage of an opportunity that presented itself and made the most of it,” said Kate Kelly, a historian who runs America Comes Alive and who previously researched Tom Carvel for the Westchester County Historical Society’s quarterly journal The Westchester Historian.

Two years later, Carvel purchased that very pottery store and converted it into a roadside ice cream stand. That same year, he formed the Carvel Brand Corporation and developed the company’s secret formula for soft-serve ice cream.

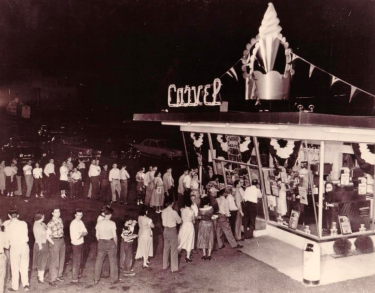

Although soft-serve ice cream was first invented in a laboratory by British chemists, it was Carvel who came up with the way to dispense it — his first real business innovation. Working alongside his brother Bruce, Carvel created a machine that was able to fast-freeze the ice cream and pump it out in small, six-ounce quantities.

Then came World War II. You wouldn’t think time spent in the military would provide Carvel with transferable skills for his ice cream business, but it did. Because of his profession prior to the war, Kelly explained, he was able to serve as a refrigeration consultant and further hone his understanding of freezing systems.

After WWII, Carvel returned home, eager to expand his business. During this time, he began to franchise his business, inspired by companies that came before, like Singer Sewing Machine, which first sold franchises in the 1850s.

“[Franchising] was certainly a thing that was very fitting for what Carvel needed to do,” Kelly said. “He couldn’t be in every place in the world dispensing ice cream, but he saw the possibilities of expanding his market by having more people selling it.”

Carvel first sold franchises within Westchester and throughout New York State, expanding along the East Coast soon thereafter. In order to train those who wished to purchase a franchise, Carvel opened the Carvel College of Ice Cream, commonly referred to as Sundae School.

Perhaps best known for its ice cream cakes with a distinctive layer of crunchies and memorable cast of characters, including Fudgie the Whale, Cookie Puss, and Hug Me The Bear, Carvel first came up with the franchising idea for these unique products himself after checking up on franchise locations near his full-time residence in Ardsley.

When he noticed that the staff, primarily teenagers and college students, was standing around during off-hours, he came up with the idea of ice cream cakes. Working with one basic mold that could be manipulated to create different shapes, employees were able to make them during slow times of the day.

“Honestly, I think the ice cream cakes are what have let him live on,” Kelly said. “That was the thing that gave him staying power.”

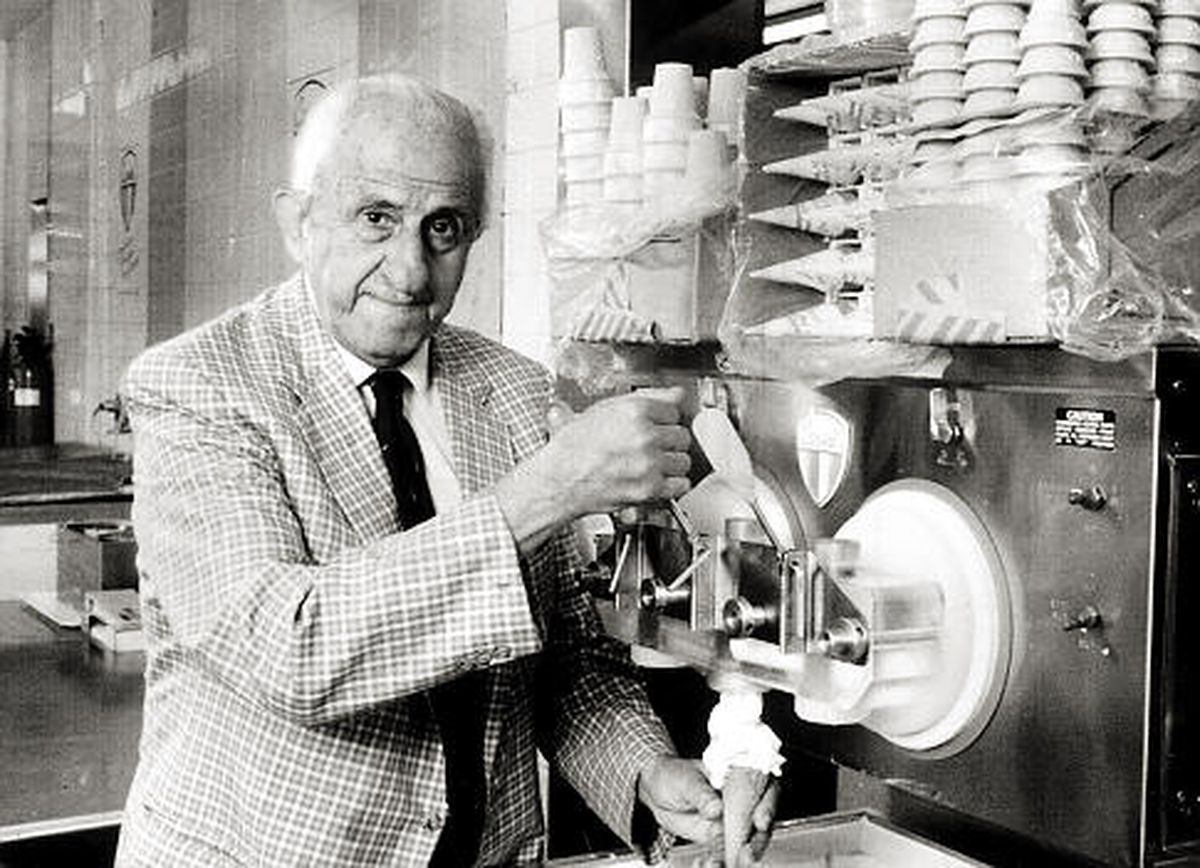

Not only was Carvel a product innovator, but he was also a keen marketer, producing his own radio ads and do-it-yourself commercials, often promoting Carvel’s buy-one-get-one-free Wednesdays.

“He had those taglines that people could remember, he was able to read them in his gravelly voice, and the people loved it,” Kelly said. “It proved that you didn’t have to have that dreamlike voice in order to sell.”

Carvel was among the first to introduce the idea that perhaps the best spokesperson for a company was the owner, with other business owners following in his footsteps like automobile executive Lee Iacocca and off-price clothing retailer Sy Syms.

Carvel and his wife Agnes had no children. In 1976, they formed the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation, where they planned to leave much of the fortune they amassed. The foundation funded causes that benefited children and families — a philanthropic nod to the primary demographic that patronized the ice cream franchise.

At its apex in 1985, there were 865 stores bringing in a combined income of over $300 million. Today, there are 322 stores, 190 of which are in New York.

Carvel sold his company to Investcorp for $80 million in 1989, and the corporate headquarters moved out of its Saw Mill River Road location in Yonkers to Farmington, Connecticut. In 2002, Investcorp sold Carvel to Roark Capital Group. At this time, Carvel Corporation splintered off into two specialties: a franchise headquarters in Atlanta and supermarket sales maintained from Rocky Hill, Connecticut.

After nearly six decades of building a massively successful ice cream empire, Tom Carvel passed away in 1990 at age 84 at his and Agnes’ weekend home in Dutchess County’s Pine Plains.

The Carvel estate, which was valued at $67 million, soon after propelled what was described as a “feeding frenzy.”

As journalist Joel Siegel wrote in a 2008 magazine article for the now-defunct Portfolio, estate battles frequently cause family members to square off against one another. In this case, Carvel’s longtime corporate secretary Mildred Arcadipane, longtime lawyer Robert Davis, and the multimillion-dollar charity that Carvel left behind were on one side, and his widow and niece Pamela Carvel on the other.

While Agnes, Pamela, and five others were appointed co-executors of his estate and co-trustees of the trust, Pamela contended that Agnes was frozen out of everything and denied millions that Tom would have wanted her to receive. Then, in 2007, following years of digging by private investigators employed by Pamela, the case took a surprising turn.

Pamela filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Fort Lauderdale, claiming that her uncle’s death resulted in “fraudsters…controlling all Carvel funds to the exclusion of the Carvels.” And to put the icing on the litigious cake, she alleged that Tom was murdered by employees who were trying to cover up a multimillion-dollar embezzlement scheme. Pamela asked the court for an exhumation and fresh autopsy.

According to Pamela, her uncle was worried in the days before his death about his safety and finances. She suspected that he was poisoned or strangled to death and alleged that his death certificate — which listed a heart attack as the cause of death — included a forged signature.

Fred Welsh, the former New Jersey police detective Pamela hired, said that he uncovered enough circumstantial evidence to suggest that someone might have fatally tampered with Carvel’s heart medicine, and he felt that was enough to warrant a homicide investigation.

Welsh also learned that friends who were staying at the Carvel home the weekend of Tom’s death received a call from a Carvel employee shortly after his death, urging them to get rid of all prescription drugs from the medicine cabinet, a request they found odd but followed anyway.

Pamela maintained that she also had circumstantial evidence against several former Carvel employees, including Arcadipane and Davis, who continued to work for the company while also battling Agnes for years over the Carvel fortune from their seats on the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation board. Eventually, both were forced to resign from their seats in 1996 in a deal with the New York attorney general’s office for misappropriating foundation money. Both died in the early 2000s, so even if future litigation found any foul play, the two could not be questioned.

When the Fort Lauderdale lawsuit was thrown out, Pamela filed another in White Plains asking for permission to have her uncle’s body dug up from Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale — a request that was never executed.

Over 40 lawyers had a hand in the Carvel case, and legal fees and commissions drained more than $28 million from the Carvel fortune by 2008. The legal battle played out in three U.S. district courts in New York, Delaware, and Florida, and in London. Four trials were held in Westchester County alone.

In 2010, a federal judge dismissed Pamela’s claims and barred her from filing any new lawsuits. Soon thereafter, Pamela filed a petition in Fort Lauderdale seeking the bankruptcy court’s protection as a Chapter 11 debtor. Instead of being granted protection, her $1.6 million Florida home was seized and auctioned to the highest bidder, and six New York City rental apartments were sold off. She was also a fugitive for civil contempt.

Almost $3 million was recovered to pay off Carvel’s creditors, including various law firms and the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation.

Critics from both inside and out of the Carvel family contended that Pamela’s bankruptcy filing was a final ploy in the larger legal war raged against the foundation, launched soon after Tom’s death over two decades prior.

While Pamela always framed herself as someone looking out for her aunt and late uncle’s best interests, family members and those involved on the other side of the litigation disagreed.

Over the years, Agnes, whom Tom would have likely wanted to be protected, found herself tangled in an endless web of legal battles. Her competency was questioned by those in charge of the two trusts that doled out her funds. Both used the same rationale — that others were manipulating Agnes, who couldn’t be trusted with her own money.

After Agnes died in 1998, posthumous matters became even more complicated. Instead of having one estate to fight over, there were now two.

While Tom Carvel, in many ways, embodied the epitome of a rags-to-riches immigrant story, the people and fortune he left behind became, much like a soft-serve ice cream cone dripping down your hand on a hot summer day, a sticky situation.

Planning experts say that Carvel made various mistakes that led to the meltdown of his estate. By appointing seven executors to manage his estate upon his death, Carvel thought he was covering all of his bases. However, the decades-long feud demonstrated that having too many people involved — especially when they have different priorities in mind — can end in disaster.

“I came here in 1991, and this case is still being litigated,” Judge Albert J. Emanuelli of the Westchester Surrogate’s Court said during court proceedings he presided over the same year Agnes passed away. “Seven years of litigation. I think it’s tragic.”

Little did Emanuelli know that the legal battle would, at last, come to a conclusion — albeit an uneventful and costlier one — over two decades after Carvel’s death.

Examiner Media is a proud participant in The Trust Project.

CLICK HERE to review our best practices and editorial policies.

This piece is a news article. CLICK HERE to learn about our definitions for types of stories.

We welcome corrections, story ideas, and general feedback. CLICK HERE to use our actionable feedback form.

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.